Filter

Contents

What Are Vertical Spreads In Options Trading And How Do They Work?

Contents

What is a Vertical Spread?

A vertical spread is an options strategy that involves opening a long (buying) and a short (selling) position simultaneously, with the same underlying asset and expiration, but at different strike prices. In this directional strategy used in options trading, both the options must be of the same type – either put or call contracts.

What’s in a name? It’s called a ‘vertical’ spread as a reference to how the strike prices are positioned – one lower and the other higher, in the same expiration cycle. A calendar spread, on the other hand, derives its directional term from the fact that the strike price would be the same on both the long and short option, but they’d have different expiration cycles.

Overview

Before we get into further details below, here is a high-level overview of the four main vertical spread types.

Long Call Vertical Spread

DEFINITION

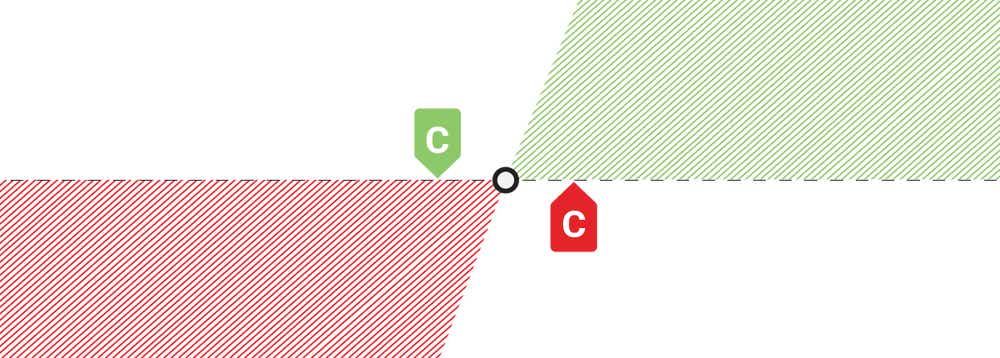

A long call vertical spread is a bullish, defined risk strategy made up of a long and short call at different strikes in the same expiration.

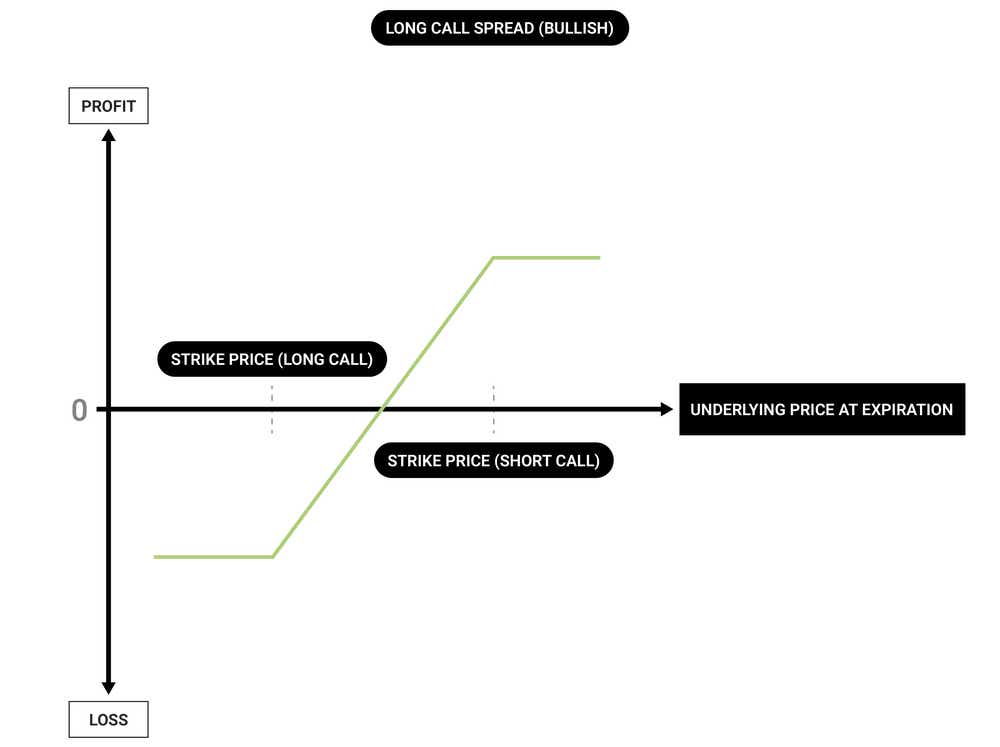

PROFIT/LOSS CHART

DIRECTIONAL ASSUMPTION

IDEAL IMPLIED VOLATILITY ENVIRONMENT

Long Put Vertical Spread

DEFINITION

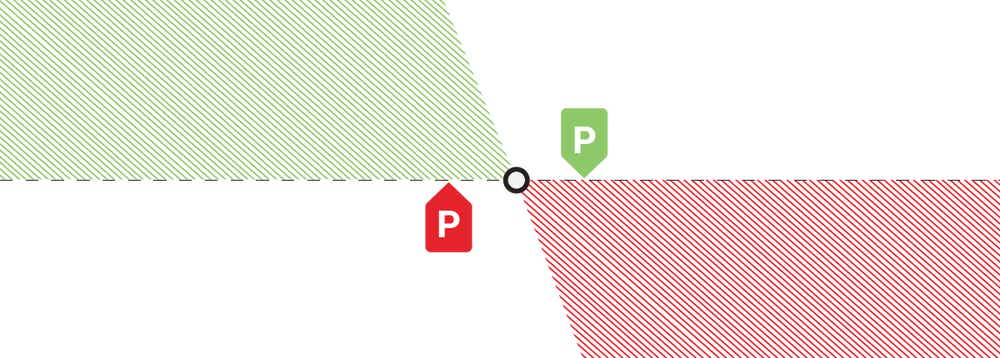

A long put vertical spread is a bearish, defined risk strategy made up of a long and short put at different strikes in the same expiration

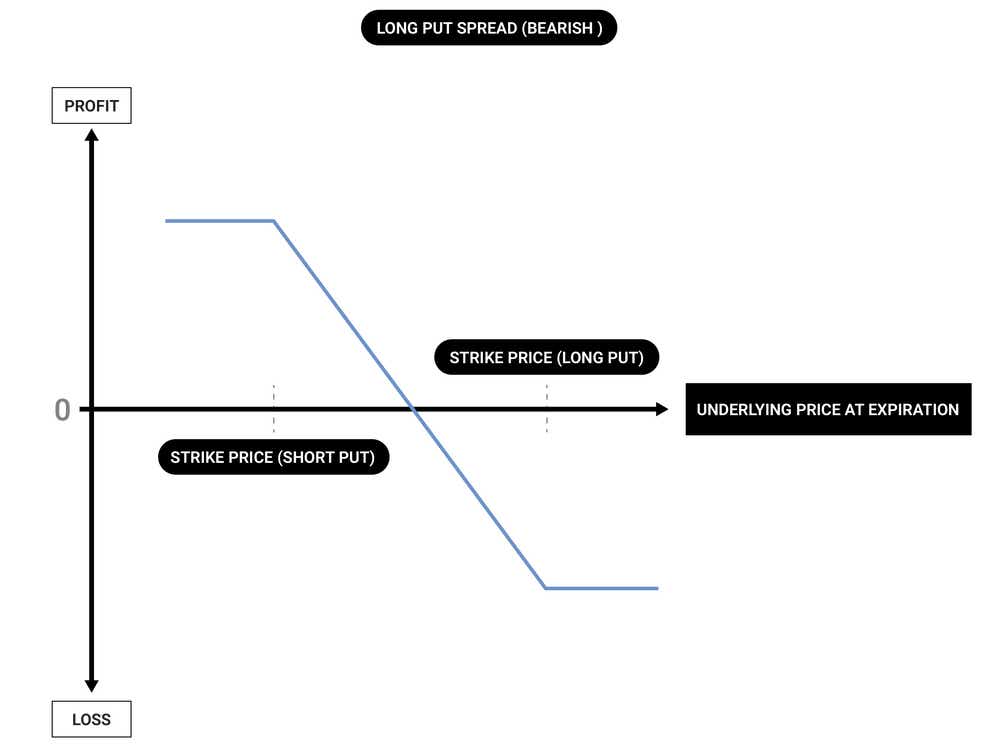

PROFIT/LOSS CHART

DIRECTIONAL ASSUMPTION

IDEAL IMPLIED VOLATILITY ENVIRONMENT

Short Call Vertical Spread

DEFINITION

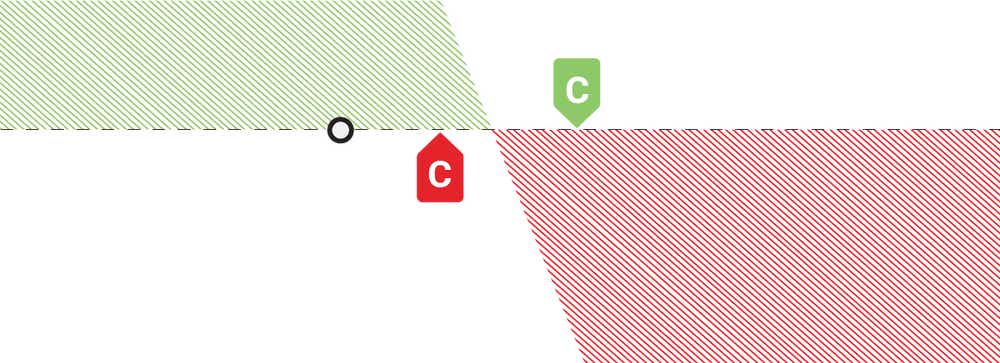

A short call vertical spread is a bearish, defined risk strategy made up of a long and short call at different strikes in the same expiration.

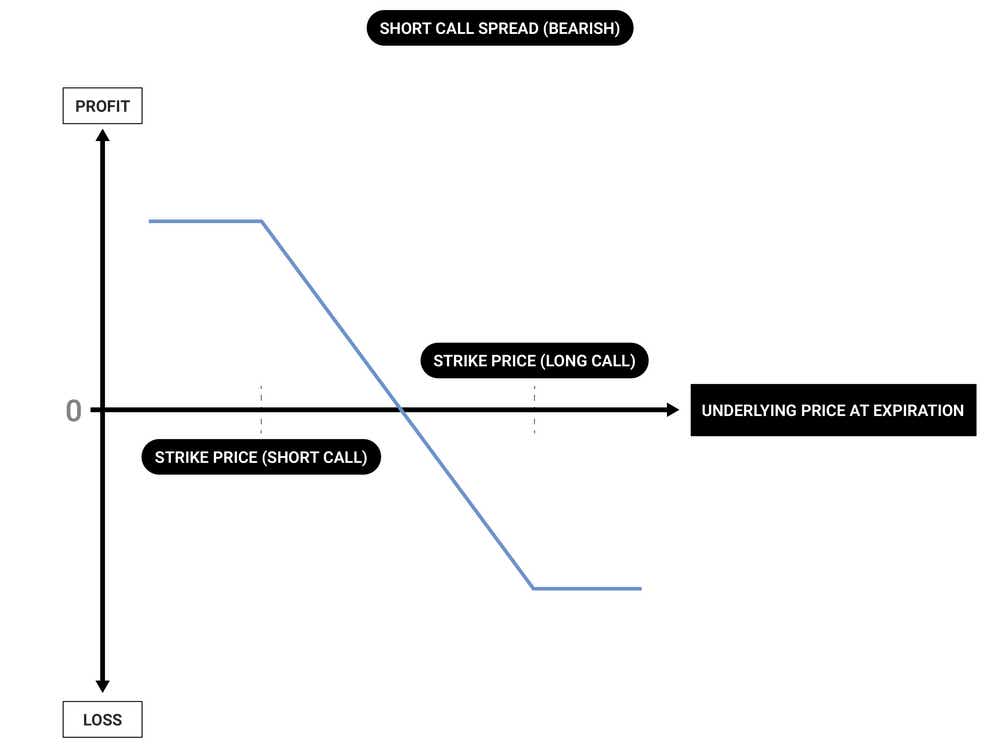

PROFIT/LOSS CHART

DIRECTIONAL ASSUMPTION

IDEAL IMPLIED VOLATILITY ENVIRONMENT

Short Put Vertical Spread

DEFINITION

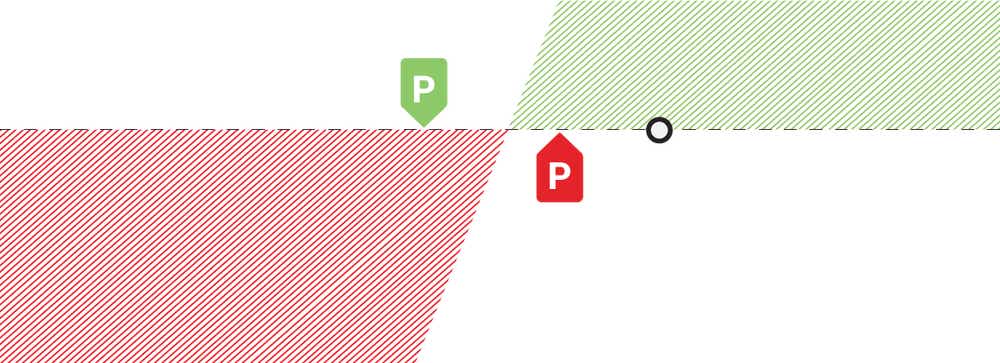

A short put vertical spread is a bullish, defined risk strategy made up of a long and short put at different strikes in the same expiration.

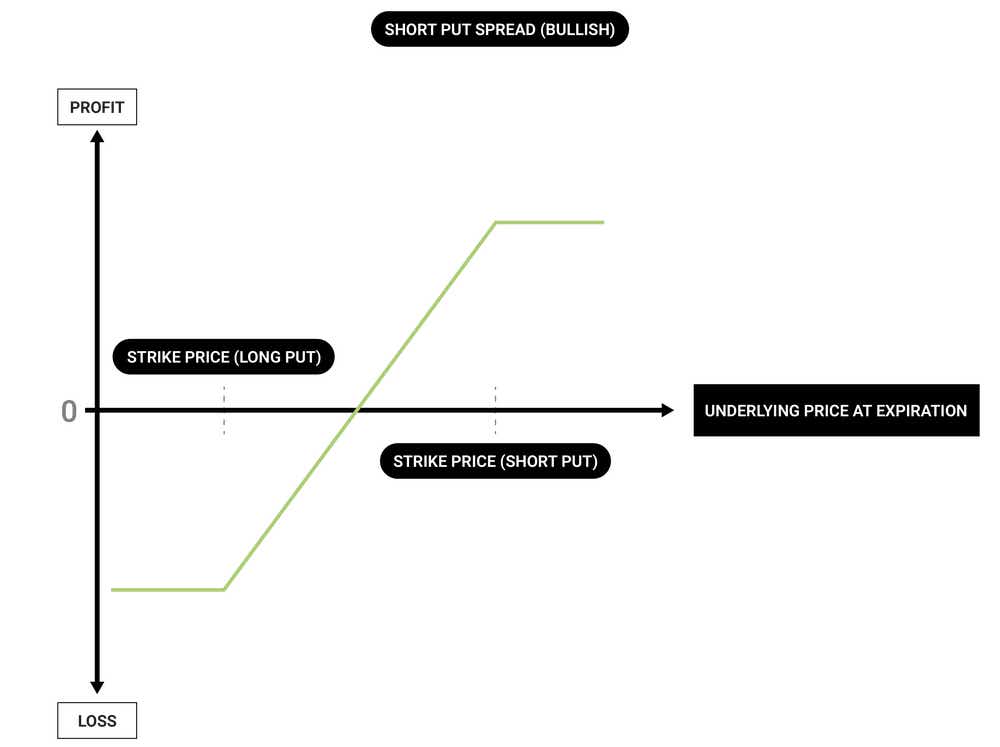

PROFIT/LOSS CHART

DIRECTIONAL ASSUMPTION

IDEAL IMPLIED VOLATILITY ENVIRONMENT

How Do Vertical Spreads Work?

Vertical spreads work by allowing you to trade directionally while clearly defining, at entry, your trade’s maximum profit as well as the highest possible loss (known as defined risk). One position offsets the other (reducing the cost basis) – this determines whether it’s a credit or debit spread.

Since the maximum loss is known at order entry, defensive tactics are somewhat limited. The max loss is known at order entry in a debit spread and credit spread – so, losing positions are generally not defended.

THE TASTYLIVE APPROACH

While implied volatility (IV) plays more of a role with naked options, it still does affect vertical spreads. We prefer to sell premium in high IV environments, and buy premium in low IV environments. When IV is high, we look to sell vertical spreads hoping for an IV contraction. When IV rank is low, we look to buy vertical spreads to stay engaged and also use it as a potential hedge against our short volatility risk.

Since the maximum loss is known at order entry, losing positions are generally not defended in debit spreads. We always look to roll for a credit in general, and doing so with vertical spreads is usually difficult.

IMPLIED VOLATILITY

Implied volatility (IV) is an options trading metric that affects options strategies, including vertical spreads. IV refers to the level of stability or explosiveness that’s estimated for an underlying asset’s future price movement over the course of an options contract. The main determining factors in calculating IV are supply and demand as well as time value.

Learn more about implied volatility

When IV is high, the market expects the underlying asset’s price to move a lot. In this environment, traders may look to sell vertical spreads hoping for an IV contraction, betting against the potential movement of the stock price. When IV is low, traders may look to buy vertical spreads to bet on IV understating realized volatility.

Discover the difference between implied and realized volatility

Vertical Spread Types and Setup

1. LONG CALL SPREAD (BULLISH)

Long Call Vertical Spread Setup

Long Call Vertical Profit and Loss

In a long call spread, you’d make the maximum profit if the market price at expiration (or execution of trade) is at or above the short call strike price. In this case, the long call would have appreciated in value as much as it could before reaching the short strike, where profits are capped.

You’d incur the maximum loss, which is the debit paid for the trade upfront, if the underlying price is at or below the long call strike price. In this debit spread, losses are limited to the position’s net cost on entry, while profits are capped at the difference between the strike prices, minus the debit paid upfront.

Discover more about long calls

LONG CALL VERTICAL SPREAD MAX PROFIT

LONG CALL VERTICAL SPREAD BREAKEVEN(S)

2. SHORT CALL SPREAD (BEARISH)

A short call vertical spread is a bearish, defined-risk strategy made up of a short and long call at different strikes within the same expiration period. Both strikes are out of the money (OTM) on setup, but the short strike is closer to the stock price than the long call.

Short Call Vertical Spread Setup

Short Call Vertical Profit and Loss

This trade is routed to collect a credit upfront. If the stock price decreases so that the value of the credit spread decreases over time, the initial credit received upfront is kept as profit at execution of the trade.

In a short call spread, maximum profit potential is the credit received upfront, if the position expires worthless and OTM at expiration. This happens when the underlying instrument’s price at expiration (or execution of trade), is equal to or below the short call’s strike price. Conversely, you’d incur the maximum loss if it’s equal to or above the long call’s strike price. In this credit spread, losses are limited to the difference between the call strikes, minus the net premium collected upfront; while profits are capped at the net premium collected upfront.

SHORT CALL VERTICAL SPREAD MAX PROFIT

SHORT CALL VERTICAL SPREAD BREAKEVEN(S)

3. LONG PUT SPREAD (BEARISH)

A long put vertical spread is a bearish, defined-risk strategy made up of a short and long put at different strikes in the same expiration cycle. The strike price of the long put is higher than the short put and the value of a long put vertical spread will increase when there’s a drop in the underlying asset’s price.

Long Put Vertical Spread

Long Put Vertical Profit and Loss

You’d make the most profit possible if the market price at expiration, or execution of the trade, is at or below the short put’s strike price. However, if it’s equal to or above the long put’s strike price, you’d incur the largest possible loss. In this debit spread, the maximum potential profit is the difference between put strikes, minus the net premium paid upfront; and losses are limited to the net premium value paid upfront.

LONG PUT VERTICAL SPREAD MAX PROFIT

LONG PUT VERTICAL SPREAD BREAKEVEN(S)

4. SHORT PUT SPREAD (BULLISH)

A short put vertical spread is a bullish, defined-risk strategy made up of a long and short put at different strikes in the same expiration. The strike price of the short put is higher than the long put and the value of a short put vertical spread will decrease when there’s a rise in the underlying asset’s price.

Short Put Vertical Spread

Short Put Vertical Profit and Loss

You’d make the most profit possible if the market price at expiration (or execution of trade) is at or above the short put’s strike price. But, if it’s equal to or below the long put’s strike price, you’d incur the largest possible loss. In this credit spread, the maximum possible profit is equal to the net premium collected upfront, while losses are limited to the difference between put strikes, minus the net premium collected upfront.

SHORT PUT VERTICAL SPREAD MAX PROFIT

SHORT PUT VERTICAL SPREAD BREAKEVEN(S)

Vertical Spread Examples

It’s vital to understand how each type of vertical spread can affect your trade’s potential for gains or losses. Let’s look at two examples that show just this, as well as what the market price of the underlying asset at expiration means for the outcome of the trade.

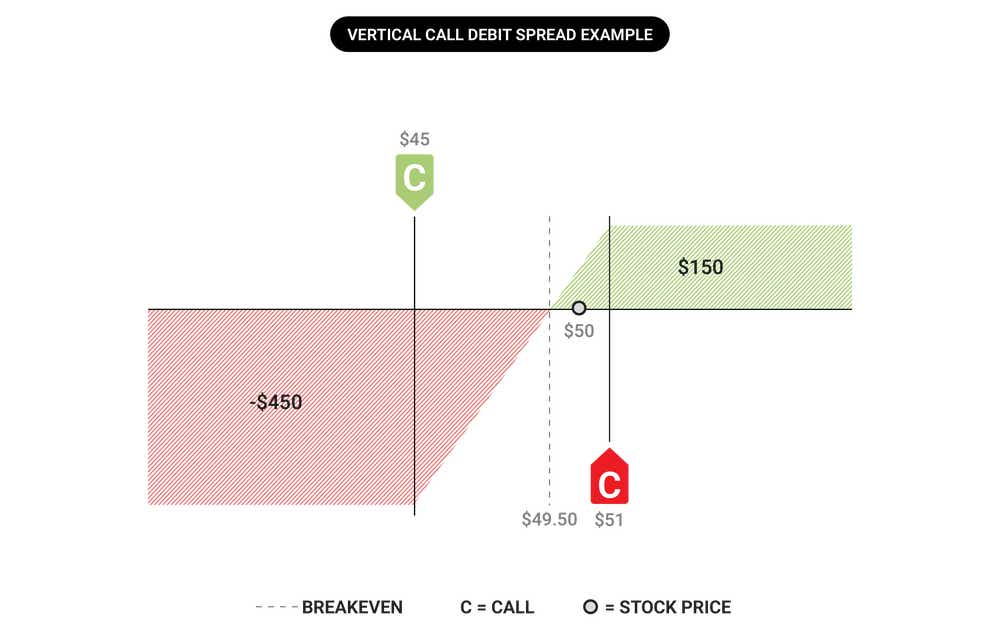

Vertical Call Debit Spread Example

Suppose you’re bullish on a particular stock. So, you decide to go long on it, employing the bull call spread strategy.

Stock price at entry: $50.00

Call strikes and prices: buy the $45.00 call at $6.50; sell the $51.00 call at $2.00

Spread entry price: $6.50 paid – $2.00 received = $4.50 net premium (net debit paid)

Breakeven price: $45.00 long call strike + $4.50 premium paid = $49.50

Maximum profit potential: ($6.00 spread width – $4.50 net premium paid) x $100.00 options contract multiplier* = $150.00

Maximum loss potential: $4.50 premium paid x $100.00 options contract multiplier* = $450.00

*The option multiplier is typically 100.

Suppose the price of the stock goes up, and reaches $53.00 at expiration, you’d make a profit.

$53.00 price at expiration – $45.00 long call strike = $8.00 expiration value

($8.00 expiration value – $4.50 premium paid) x $100.00 options contract multiplier = $350.00

But, since there’s a maximum profit potential for this trade if the new stock price is at or above the short call strike, your profit will be:

($6.00 spread width – $4.50 premium paid) x $100 = $150.00 profit

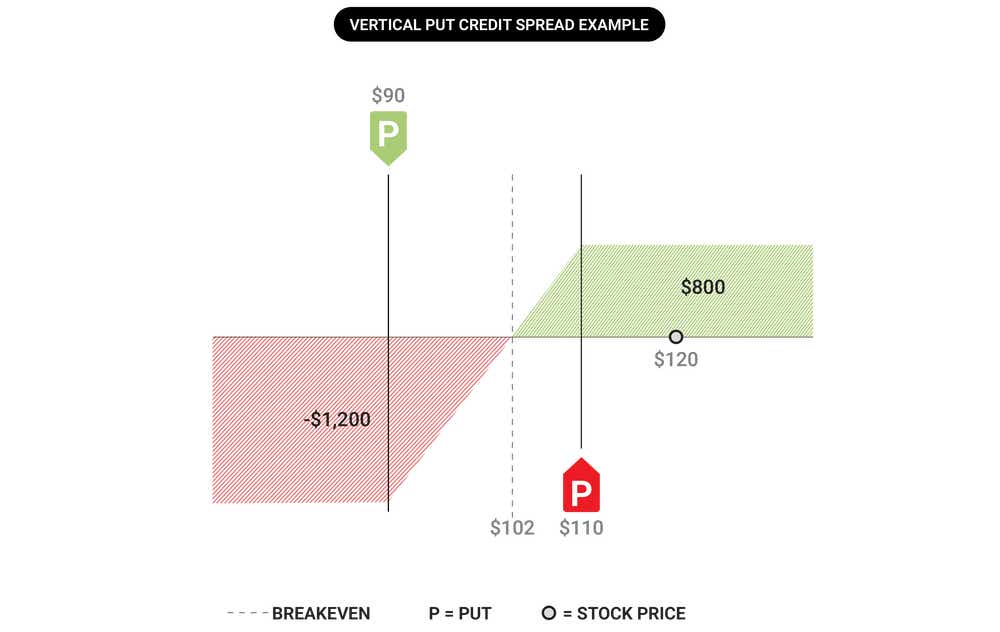

Vertical Put Credit Spread Example

Suppose you’re bullish on a particular stock. So, you decide to employ the bull put spread strategy.

Stock price at entry: $120.00

Put strikes and prices: sell the $110.00 put for $12.00; buy the $90.00 put for $4.00

Spread entry price: $12.00 received – $4.00 paid = $8.00 net premium (net credit received)

Breakeven price: $110.00 short put strike – $8.00 net credit received = $102.00

Maximum profit potential: $8.00 net premium received x $100.00 options contract multiplier = $800.00

Maximum loss potential: ($20.00 spread width – $8.00 net premium paid) x $100.00 options contract multiplier = $1200.00

Since there’s a maximum profit potential for this trade if the new stock price is at or above the short put strike, you’ll get:

$8.00 net premium received x $100.00 options contract multiplier = $800.00 profit

Credit Spreads vs Debit Spreads: What’s The Difference?

CREDIT SPREADS

In a credit spread, the premium received from the selling position is more than the premium to buy (long position). The difference results in a net short premium position, or a credit trade. A short call spread, and a short put spread are credit spreads, because the short options are worth more than the long options purchased to define the risk.

The short option and net credit received are the focal points of a credit spread, and the credit received upfront pushes our breakeven price beyond the short strike. The long option defines our risk in a credit spread, and is like our insurance policy against the short option.

Debit Spreads

In a debit spread, the long option costs more (premium to buy) than the short option (premium received from selling) therefore, the net premium is a debit. Long call spreads and long put spreads are debit spreads because the long options are worth more than the short option that’s sold against it to reduce the cost basis.

The long option is the asset in a debit spread. The cost basis of the long option is reduced by selling the short option against it. Remember, the maximum loss (i.e. the net premium paid) is known at order entry in debit spreads – therefore, losing positions are typically not defended.

When to Close and When to Manage Vertical Spreads

Closing

All four types of profitable vertical spreads will be closed at a more favorable price than the entry price (goal: 50% of maximum profit). For example, if the credit received from a short vertical spread was $150, 50% of maximum profit would be $75. For debit spreads, if the maximum profit was $250, traders would look to close the position when the spread makes $125.

Keep in mind that the 50% guideline is not a rule, and profits can be taken at any point during the duration of the trade.

Managing

As stated above, losing long vertical spreads will not be managed but can be closed any time before expiration to avoid assignment/fees.

Managing Credit Spreads

Managing credit spreads can decrease your possible maximum loss and increase your highest potential profit. You can set alerts on the tastytrade platform to help you manage your credit spreads.

What’s important to remember with managing a credit spread is to not let the it go completely ITM. This typically happens if your long option has more extrinsic value than your short option.

If the short option to has more extrinsic value than the long option, you can roll the spread out in time for a credit. In other words, you’d be collecting more extrinsic value from the premium received than you’d be paying in the buying position. This reduces your max loss potential, while increasing your highest possible profit.

VERTICAL SPREADS SUMMED UP

- A vertical spread involves having two call or put positions (buy and sell) of the same underlying asset and expiration, but different strike prices, open simultaneously

- Vertical spreads are directional strategies used in options trading

- There are four basic types of vertical spreads: long call spread, short call spread, long put spread and short put spread

- Whether you make a profit or incur a loss from a market movement prediction depends on the type of vertical spread you’re employing and where the stock price is at expiration relative to your spread strikes

- Profits and losses are capped at certain values based on the relevant calculations, as a vertical spread is a risk-defining strategy

- The two legs of the position (buying and selling) determine whether it’s a credit or debit spread. If the long option is worth more than the short option, it’s a debit trade. If the short option is worth more than the long option, it’s a credit trade

FAQs

What is a vertical spread example?

A vertical spread example is one where a call spread or put spread is explored – these can either be bullish or bearish.

How can I make money using vertical spreads?

You can make a profit from a vertical spread if you have a bullish position and the underlying asset’s price rises, or if you have a bearish position and the underlying asset’s price falls. Naturally, if the market moves against your position, you’d incur a loss.

Are vertical spreads bullish or bearish?

Vertical spreads can be bullish or bearish depending on the type of strategy. The four basic types of vertical spreads are:

- Long call spreads: bullish (vertical call debit spread)

- Short call spread: bearish (vertical call credit spread)

- Long put spread: bearish (vertical put debit spread)

- Short put spread: bullish (vertical put credit spread)

Should I let a vertical spread expire?

Typically, vertical spreads are closed prior to expiration to avoid unwanted assignment of shares. You can hold your vertical spreads closer to expiration if you haven’t yet reached your profit target. But you have to be mindful of how holding vertical spreads through expiration can result in unwanted shares if just one option expires ITM and the other expires worthless.

It is also important to note that you need to have enough net liquidity in your tastytrade account to hold a spread through expiration. This is to account for the potential execution of trade or assignment.

What is a vertical spread strategy?

A vertical spread strategy is used in options trading. It’s opening two of the same options type (call or put) positions – one long and one short – on the same underlying asset, with an identical expiration, but different strike prices.

How do I close/stop a vertical spread?

You can close a vertical spread at any point before expiration by routing the opposite order that you executed on entry. If you bought a call spread to open, you can sell the call spread to close. If you sold a put spread to open, you can buy back the put spread to close.

You can do this manually, or by using a stop order once a price level that’s more favorable than the entry price is reached. Another reason to stop a vertical spread is to manage your risk by cutting losses.

What does rolling a vertical spread mean?

Rolling a vertical spread means closing your current spread position and moving it to a further-dated expiration or to different strikes. This is a way of managing winning or losing positions if you’ve had a change of heart about how you think the market will be moving.

How do I roll a vertical spread?

Can I close one leg of a vertical spread?

Yes – you can leg out of a vertical spread, but it’s not something that’s typically considered. This turns a defined-risk trade into an undefined-risk trade if the remaining option is a short option, which that can multiply risk. Risk can also be multiplied if the short option is closed on a vertical debit spread, as the long option could be worth a lot more than the spread’s initial cost. This is a high-risk or high-reward adjustment in many cases, so be aware of how the trade will change if you consider legging out.

Can I sell a credit spread before expiration?

Yes – you can close a credit spread or debit spread before the expiration of the contracts. This allows you to secure profits already made or limit potential losses. Closing a vertical spread just means routing the opposite order in the same expiration. To close a vertical credit spread, you would buy back the same strike debit spread. To close a vertical debit spread, you would sell the same strike credit spread.

When do I get assigned on a spread?

American-style short options can be assigned at expiration or at any point before expiration. Whereas, assignment on European-style short options can only happen at expiration.

In cases where spreads have their short leg assigned early (American-style short options), you can close out the position along with the long option as a covered stock order. You’d retain the same max loss on the spread as when it was opened.

Why isn’t my vertical spread closing before expiration?

If you have an OTM spread going into expiration, for example, and you’re trying to close it, the order may not fill if you’re including a long option with no bid. In this case, you can buy back (cover) your short option to eliminate any assignment risk.