Filter

Backwardation

What is Backwardation?

Backwardation is a term used to describe the structure of prices in the market across the time horizon, and is most often associated with commodities and futures markets.

In backwardation, the futures price is lower than the expected spot price of the underlying asset at the contract's expiration. That means the futures contract trades at a discount to the spot price.

This is somewhat unusual because in "normal" futures markets, it's the reverse situation—referred to as "contango." Contango exists the majority of the time in most markets because asset prices are generally expected to rise over time (due to inflation and other market factors).

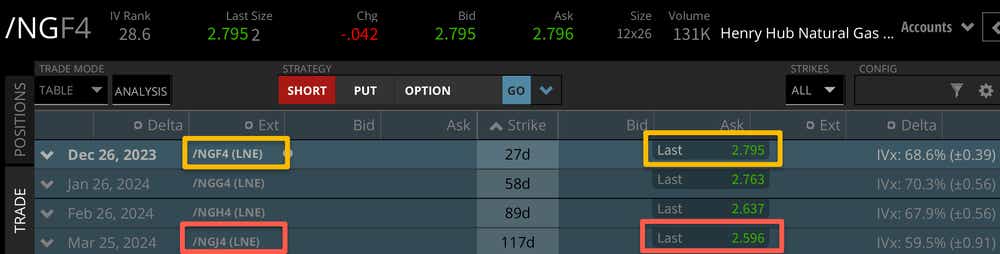

For example, natural gas futures markets trade in contango most of the time—meaning prices are projected to increase the further one goes out on the time horizon, but in volatile times you may see this flip into backwardation. This is where near-term futures contracts have a higher price than contracts further out in time.

How Does Backwardation Work?

Backwardation can develop for a variety of reasons.

For example, if a particular commodity is in short supply, market participants may be willing to pay a premium for immediate delivery of that commodity. In cases like this, suppliers may demand a premium for immediate delivery of a commodity that’s in short supply, which is why the near-term price (or spot price) of a commodity might be higher than longer-dated futures contracts.

In a “normal” market, longer-dated futures contracts are generally priced higher than current spot prices in the market, due to inflation and the risk of other unknown market factors that may develop over time.

Markets tend to move into backwardation when there’s widespread agreement that an asset’s price will decline in the future. For example, if an economic recession is expected to develop at some point in the future, the market may move into backwardation to account for slowing demand, which often has a negative impact on prices.

Supply disruptions, weather events, and geopolitical events can also contribute to backwardized markets.

Futures Price vs Spot Price

The spot price refers to the current price for immediate delivery, while the futures price refers to the price at which a futures contract for an asset can be bought or sold.

A futures contract is a standardized agreement to buy or sell an asset (such as commodities, currencies, or financial instruments) at a predetermined price on a future date. The futures price is determined through the interaction of buyers and sellers in the futures market, and it represents the market's expectation of the asset's value at the contract's expiration.

The futures price typically differs from the spot price due to a variety of factors, including supply/demand, interest rates, storage costs, market sentiment, and market participants' outlook on the asset's future value.

What Causes Backwardation?

Backwardation can develop for a variety of reasons.

For example, if a particular commodity is in short supply, market participants may be willing to pay a premium for immediate delivery of that commodity. In cases like this, suppliers may demand a premium for immediate delivery of a commodity that’s in short supply, which is why the near-term price (or spot price) of a commodity might be higher than longer-dated futures contracts.

In a “normal” market, longer-dated futures contracts are generally priced higher than current spot prices in the market, due to inflation and the risk of other unknown market factors that may develop over time.

Markets tend to move into backwardation when there’s widespread agreement that an asset’s price will decline in the future. For example, if an economic recession is expected to develop at some point in the future, the market may move into backwardation to account for slowing demand, which often has a negative impact on prices.

Supply disruptions, weather events, and geopolitical events can also contribute to backwardation.

Example of a Backwardized Market

Looking at an example, imagine crude oil is currently trading $70 per barrel (for immediate delivery). In backwardation, longer-dated futures contracts will be priced lower than near-term futures contracts.

In this scenario, the one-month futures contract might be priced at $69 per barrel, while the six-month futures contract might be priced at $67 per barrel.

As a result, the market is said to be in backwardation because the future prices of oil are lower than the spot price.

How to Profit from Backwardation?

There’s no guaranteed method of profiting from a market in backwardation, just as there’s no guaranteed method of profiting from a contango market.

Moreover, the investing/trading approach adopted in any market environment will depend heavily on a given investor/trader’s outlook and risk profile.

However, investors and traders can consider several different approaches in a backwardized market to try and make a profit—assuming one of the strategies fits the investor/trader’s outlook and risk profile.

For example, assuming that an investor/trader already holds an existing long position in a backwardized market, he/she might decide to exit (i.e. sell) that position in favor of purchasing a longer-dated futures contract at a lower price—especially if he/she is bullish on the future price of the underlying asset.

This is essentially a “roll yield” trading approach. A roll yield occurs when you roll your existing futures position from a near-term contract to a longer-dated contract. For example, as the near-term contract approaches expiration, you can sell it and simultaneously buy the next contract with a lower futures price, allowing you to capture the backwardation spread.

Alternatively, one might decide to simply exit the existing position, and wait until the market returns to contango.

Advanced futures traders may also elect to execute a spread when markets move into backwardation. Futures spreads are executed by simultaneously deploying two opposing positions (one long, one short) in the same underlying futures market. Typically this involves buying or selling a near-term futures contract and taking the opposite position in a longer-dated futures contract.

If the prices of the contracts converge over time, a futures spread will generally produce a profit. But if the prices in the spread diverge, it will create a loss.

Contango vs Backwardation: What Are the Differences?

In backwardation, the futures price is lower than the expected spot price of the underlying asset at the contract's expiration. That means the futures contract trades at a discount to the spot price.

This is somewhat unusual because in "normal" futures markets, it's the reverse situation—referred to as "contango." Contango exists the majority of the time in most markets because asset prices are generally expected to rise over time (due to inflation and other market factors).

In a contango market, the futures price is higher than the expected spot price of the underlying asset at the contract's expiration. This means that the futures contract trades at a premium to the spot price.

For example, the majority of the time, crude oil futures markets trade in contango—meaning prices are projected to increase the further one goes out on the time horizon.

Backwardation Summed up

- The spot price refers to the current price for immediate delivery, while the futures price refers to the price at which a futures contract for an asset can be bought or sold

- In backwardation, the futures price is lower than the expected spot price of the underlying asset at the contract's expiration. That means the futures contract trades at a discount to the spot price

- This is somewhat unusual because in "normal" futures markets, it's the reverse situation—referred to as "contango." Contango exists the majority of the time in most markets because asset prices are generally expected to rise over time (due to inflation and other market factors)

- For example, the majority of the time, crude oil futures markets trade in contango—meaning prices are projected to increase the further one goes out on the time horizon

- Backwardation can develop for a variety of reasons

- For example, if a particular commodity is in short supply, market participants may be willing to pay a premium for immediate delivery of that commodity. In cases like this, suppliers may demand a premium for immediate delivery of a commodity that’s in short supply, which is why the near-term price (or spot price) of a commodity might be higher than longer-dated futures contracts

- Markets tend to move into backwardation when there’s widespread agreement that an asset’s price will decline in the future. For example, if an economic recession is expected to develop at some point in the future, the market may move into backwardation to account for slowing demand, which often has a negative impact on prices

- Supply disruptions, weather events, and geopolitical events can also contribute to backwardized markets

FAQ

What happens during backwardation?

In backwardation, the futures price is lower than the expected spot price of the underlying asset at the contract's expiration. That means the futures contract trades at a discount to the spot price.

This is somewhat unusual because in "normal" futures markets, it's the reverse situation—referred to as "contango." Contango exists the majority of the time in most markets because asset prices are generally expected to rise over time (due to inflation and other market factors).

For example, the majority of the time, crude oil futures markets trade in contango—meaning prices are projected to increase the further one goes out on the time horizon.

Markets tend to move into backwardation when there’s widespread agreement that an asset’s price will decline in the future. For example, if an economic recession is expected to develop at some point in the future, the market may move into backwardation to account for slowing demand, which often has a negative impact on prices.

Supply disruptions, weather events, and geopolitical events can also contribute to backwardized markets.

How can I profit from backwardation?

There’s no guaranteed method of profiting from a backwardized market, just as there’s no guaranteed method of profiting from a contango market.

Moreover, the investing/trading approach adopted in any market environment will depend heavily on a given investor/trader’s outlook and risk profile.

However, investors and traders can consider several different approaches in a backwardized market to try and make a profit—assuming one of the strategies fits the investor/trader’s outlook and risk profile.

For example, assuming that an investor/trader already holds an existing long position in a backwardized market, he/she might decide to exit (i.e. sell) that position in favor of purchasing a longer-dated futures contract at a lower price—especially if he/she is bullish on the future price of the underlying asset.

This is essentially a “roll yield” trading approach. Alternatively, one might decide to simply exit the existing position, and wait until the market returns to contango.

Advanced futures traders may also elect to execute a spread in a backwardized market. Futures spreads are executed by simultaneously deploying two opposing positions (one long, one short) in the same underlying futures market. Typically this involves buying or selling a near-term futures contract and taking the opposite position in a longer-dated futures contract.

If the prices of the contracts converge over time, a futures spread of this type will generally produce a profit. But if the prices in the spread diverge, it will create a loss.

What are the risks of backwardation?

Some of the risks in a backwardized market include insufficient liquidity and higher than average volatility.

Markets in backwardation can also experience heightened volatility due to supply disruptions, geopolitical events, or sudden changes in market sentiment. Price fluctuations can occur swiftly, potentially leading to increased risk and significant capital losses. Investors and traders should therefore be prepared for heightened volatility in backwardized markets, and have appropriate risk management strategies in place.

Backwardized markets may also present reduced liquidity, which can result in wider bid-ask spreads, reduced trading volumes, and difficulty in entering or exiting positions at desired prices. Investors and traders should therefore assess potential liquidity issues prior to entering positions in backwardized markets, as this type of environment may present increased execution risk, and therefore an increased risk of capital losses.

Moreover, backwardized markets present the risk of reversal—basically a swing back to contango market conditions. The risk of a reversal, or sudden change from the current trend, is possible in any market, but especially in backwardation, and they tend to be temporary in nature.

That said, contango markets may also experience sharp price changes due to unexpected developments in the market. For this reason, investors and traders should adhere to disciplined risk management practices in all market environments.

Why would a market be in backwardation?

Backwardation can develop for a variety of reasons.

For example, if a particular commodity is in short supply, market participants may be willing to pay a premium for immediate delivery of that commodity. In cases like this, suppliers may demand a premium for immediate delivery of a commodity that’s in short supply, which is why the near-term price (or spot price) of a commodity might be higher than longer-dated futures contracts.

In a “normal” market, longer-dated futures contracts are generally priced higher than current spot prices in the market, due to inflation and the risk of other unknown market factors that may develop over time.

Markets tend to move into backwardation when there’s widespread agreement that an asset’s price will decline in the future. For example, if an economic recession is expected to develop at some point in the future, the market may move into backwardation to account for slowing demand, which often has a negative impact on prices.

Supply disruptions, weather events, and geopolitical events can also contribute to backwardized markets.

tastylive content is created, produced, and provided solely by tastylive, Inc. (“tastylive”) and is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, trading or investment advice or a recommendation that any security, futures contract, digital asset, other product, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any person. Trading securities, futures products, and digital assets involve risk and may result in a loss greater than the original amount invested. tastylive, through its content, financial programming or otherwise, does not provide investment or financial advice or make investment recommendations. Investment information provided may not be appropriate for all investors and is provided without respect to individual investor financial sophistication, financial situation, investing time horizon or risk tolerance. tastylive is not in the business of transacting securities trades, nor does it direct client commodity accounts or give commodity trading advice tailored to any particular client’s situation or investment objectives. Supporting documentation for any claims (including claims made on behalf of options programs), comparisons, statistics, or other technical data, if applicable, will be supplied upon request. tastylive is not a licensed financial adviser, registered investment adviser, or a registered broker-dealer. Options, futures, and futures options are not suitable for all investors. Prior to trading securities, options, futures, or futures options, please read the applicable risk disclosures, including, but not limited to, the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options Disclosure and the Futures and Exchange-Traded Options Risk Disclosure found on tastytrade.com/disclosures.

tastytrade, Inc. ("tastytrade”) is a registered broker-dealer and member of FINRA, NFA, and SIPC. tastytrade was previously known as tastyworks, Inc. (“tastyworks”). tastytrade offers self-directed brokerage accounts to its customers. tastytrade does not give financial or trading advice, nor does it make investment recommendations. You alone are responsible for making your investment and trading decisions and for evaluating the merits and risks associated with the use of tastytrade’s systems, services or products. tastytrade is a wholly-owned subsidiary of tastylive, Inc.

tastytrade has entered into a Marketing Agreement with tastylive (“Marketing Agent”) whereby tastytrade pays compensation to Marketing Agent to recommend tastytrade’s brokerage services. The existence of this Marketing Agreement should not be deemed as an endorsement or recommendation of Marketing Agent by tastytrade. tastytrade and Marketing Agent are separate entities with their own products and services. tastylive is the parent company of tastytrade.

tastyfx, LLC (“tastyfx”) is a Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) registered Retail Foreign Exchange Dealer (RFED) and Introducing Broker (IB) and Forex Dealer Member (FDM) of the National Futures Association (“NFA”) (NFA ID 0509630). Leveraged trading in foreign currency or off-exchange products on margin carries significant risk and may not be suitable for all investors. We advise you to carefully consider whether trading is appropriate for you based on your personal circumstances as you may lose more than you invest.

tastycrypto is provided solely by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. tasty Software Solutions, LLC is a separate but affiliate company of tastylive, Inc. Neither tastylive nor any of its affiliates are responsible for the products or services provided by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. Cryptocurrency trading is not suitable for all investors due to the number of risks involved. The value of any cryptocurrency, including digital assets pegged to fiat currency, commodities, or any other asset, may go to zero.

© copyright 2013 - 2025 tastylive, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Applicable portions of the Terms of Use on tastylive.com apply. Reproduction, adaptation, distribution, public display, exhibition for profit, or storage in any electronic storage media in whole or in part is prohibited under penalty of law, provided that you may download tastylive’s podcasts as necessary to view for personal use. tastylive was previously known as tastytrade, Inc. tastylive is a trademark/servicemark owned by tastylive, Inc.