Filter

Contents

What Are Put Options And How Do They Work?

Contents

WHAT IS A PUT OPTION?

A put option is a derivative contract that lets the owner sell 100 shares of a particular underlying asset at a predetermined price (known as the strike price) on or before the expiration date. Put options give the owner the right, but not the obligation, to realize the theoretical equivalent of 100 shares of short stock below the strike price, less the extrinsic value premium paid for the contract itself.

Unlike with call options, where a long position means that the trader’s directional assumption is bullish, long put options reflect a bearish market expectation. If the asset’s price goes down, the put increases in value. On the other hand, if it rises, the value of the put option decreases, which (in this case) is in favor of the short put position. Just like call options, traders can be long or short put contracts, depending on their trading goals.

The right to sell the underlying asset is secured through paying a premium to hold the theoretical equivalent of 100 short shares of stock below the put strike for a limited amount of time. Since put buyers don’t have an obligation to short-sell the 100 shares, they can go the alternative route of letting the option expire worthless and only give up the premium paid up front. This is typically done if the stock price stays above the strike price. They can also sell the put contract to close the position and retain any extrinsic value remaining.

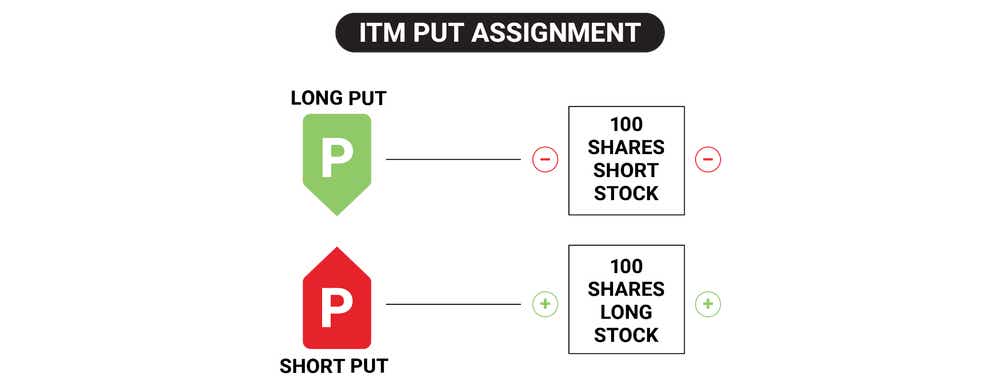

If the stock price falls well below the strike and the put buyer exercises their right to sell, the counterparty is obligated – through assignment – to buy 100 shares from the put contract owner, resulting in 100 short shares for the put contract owner. The put owner can also sell the contract instead of taking short shares to close the position – if the put is worth more than what the trader bought it for up front, the transaction results in a profit.

The three key characteristics of options contracts are:

- Strike price: the predetermined price at which the buyer and seller exchange the underlying asset, i.e. 100 shares of stock per contract

- Expiration date: the day on which the contract settlement takes place, or the contract expires worthless

- Premium: the amount paid per contract to become an option owner

PROFIT/LOSS CHARTS

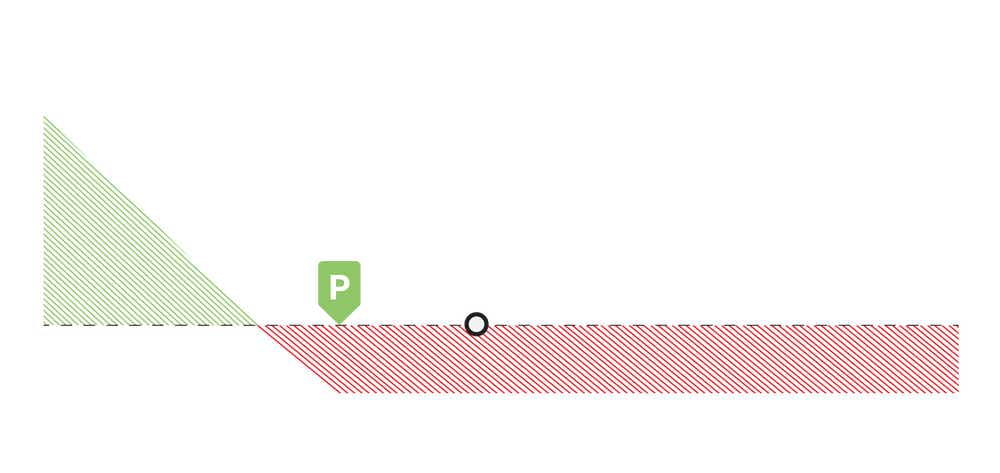

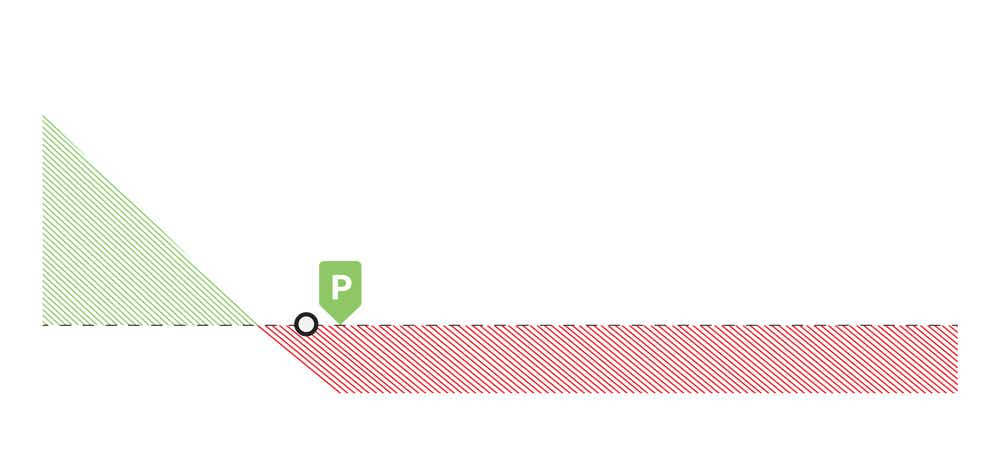

Long Put Options

OTM |

ITM |

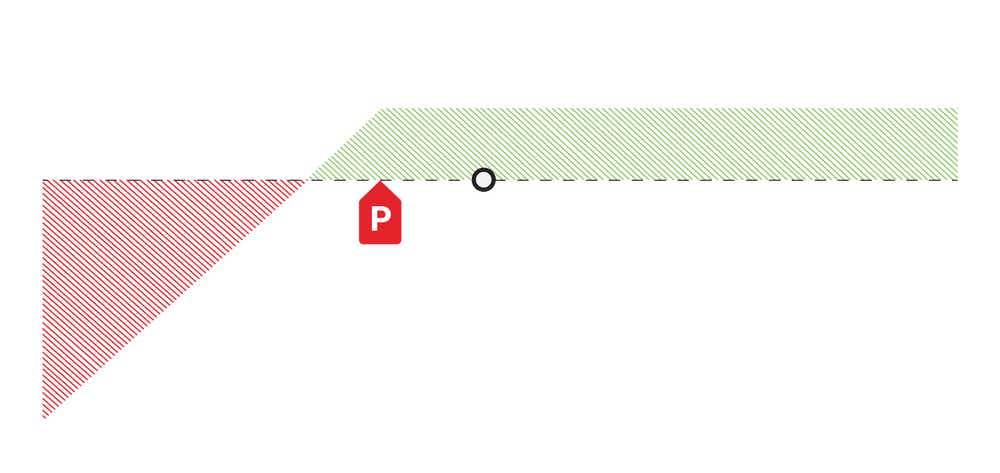

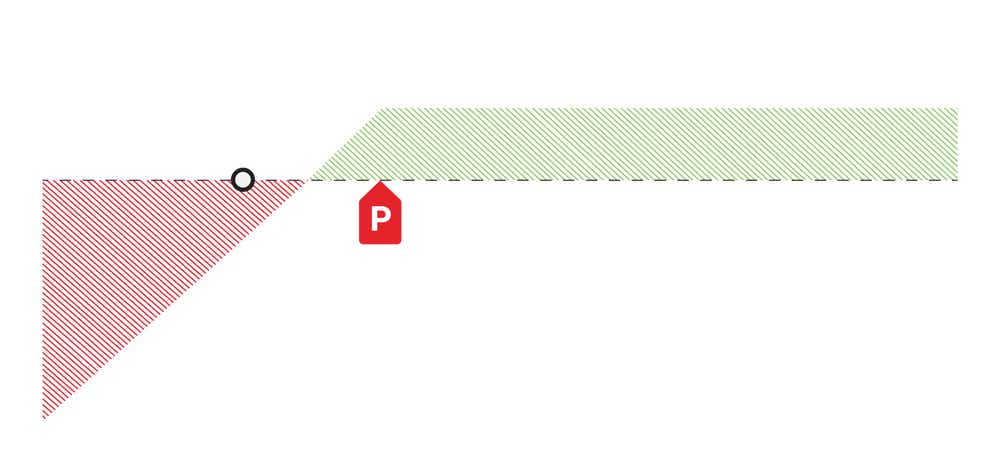

Short Put Options

OTM |

ITM |

HOW DO PUT OPTIONS WORK?

Put options work through an agreement, between a buyer and a seller, to exchange an underlying asset at a predetermined price by a certain expiration date. Traders commonly buy put options if they think an underlying's price will experience a significant drop in the near-term and implied volatility (IV) will increase prior to the option’s expiration date. For most products, a drop in the stock price can result in an increase in IV. Put owners don’t have to own the physical asset to secure the right to sell it if they exercise the option, which limits their monetary risk. Many people just trade the put contract itself though, and don’t end up taking shares at expiration.

Contract settlement can happen in one of three ways. The option owner can:

- Exercise the option if it moves in-the-money (ITM)

- Sell the contract before expiry, or

- Let it expire worthless if the stock price remains above the put strike price, foregoing only the premium paid up front

The two parties in an options contract have opposite market assumptions – so when one profits, the other incurs a loss. While the put only has intrinsic value for the option buyer if the stock price is below the strike price at expiration, put sellers want the strike to remain out-of-the-money (OTM) – they benefit if the stock price remains above the strike price at expiry as they collect a credit up front for selling the contract, and as long as that contract remains OTM they keep the credit as profit through expiration.

Implied Volatility in Long Calls

Implied volatility (IV) is among the typical considerations when putting together a trading plan. Some traders aim to place long puts, or long put spreads, in low IV environments, i.e. underlyings with low IV rank and/or low IV that may be near 52-week highs. The amount of extrinsic value paid for the put or put spread is lower for underlyings with a low IV rank compared to those with high IV rank. Larger market price shifts are expected in the underlying as IV increases, and vice versa, which means that put option owners may be able to sell the contract at a higher premium, especially if the increase in IV is due to the stock price selling off.

BUYING A PUT OPTION (LONG PUT)

Buying a long put is typically indicative of a bearish market expectation. To be profitable with a long put contract, the underlying asset's price will need to have a significant downwards move that crosses the put strike on or before the expiration date of the contract. Long put buyers essentially hope for the put to be deep in-the-money (ITM) well ahead of, or at the contract’s expiration date, so that the contract has real intrinsic value to the owner. The put buyer stands to profit if the option price is worth more than the cost paid upfront to purchase it.

Long Put Example

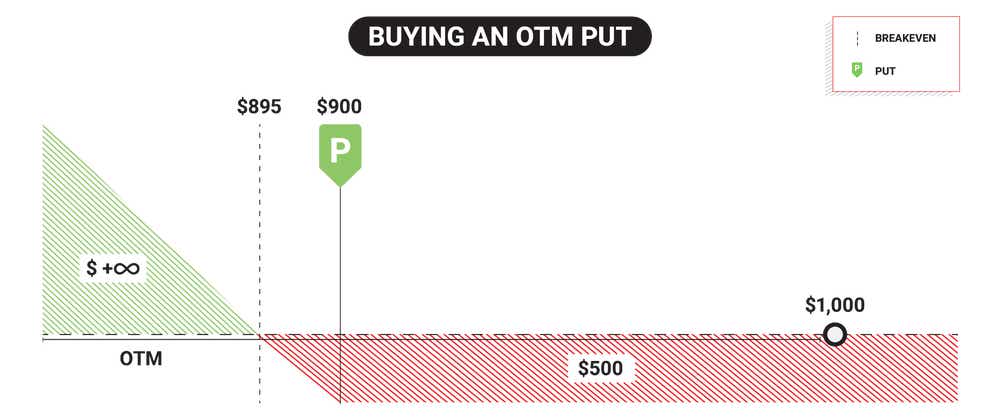

Imagine you believe that Company XYZ’s stock price is on the verge of dropping substantially. With its current price at $1,000, you think it’ll drop below $900 in the near-term.

Buying one long put gives you exposure to the theoretical equivalent of 100 shares of short stock at a significantly lower cost up-front, as you wouldn’t own the shares outright. Owning 100 physical shares at the current market price translates into $100,000 of total risk. However, a put option also gives you exposure to 100 shares, only for much less.

Suppose you buy a 30-day put option on Company XYZ stock at a premium, i.e. debit paid, of $5 per share ($500 in real dollar terms) and a strike price of $900. If the stock experiences a price drop that passes the strike price by more than $5 by the expiration date, you can sell the contract at a higher premium for a net profit.

If the stock, however, doesn’t fall below the $900 strike, the value of the put can still increase considerably if there’s a sharp bearish move in the underlying’s price with a lot of time left to expiration. Assuming that this swift decrease moved the stock price past the put strike to $880, you could sell the contract for at least $20 or $2,000 of intrinsic value, plus any remaining extrinsic value in the contract itself. Let’s say there’s also $2,500 of extrinsic value remaining in the contract. This would result in a profit of $4,000 (after subtracting your cost to enter the put contract). If you held this to expiration, you would lose all the extrinsic value, and if the stock is still at $880, you would realize a profit of $1,500 if you sold the contract for its intrinsic value of $2,000.

Suppose you hang on to the contract through expiration, but the stock price remains well above the strike price. The option would expire worthless and you’d only forego the $500 premium paid upfront for exposure to the theoretical equivalent of 100 shares of short stock.

WHEN TO CLOSE A LONG PUT OPTION

A long put owner can decide to sell the options contract at any point before expiration, where they’d either make a profit or incur a loss. Of course, the aim is to make a profit, which in this case would happen if the trade is closed when the value of the put is more than the entry price paid to buy the contract.

Long put options can be closed in one of three ways:

In all three ways of closing a put option, potential profits or losses are dependent on the underlying’s price when the closing transaction takes place (or expiry in the first case). Choosing the third option above means that the put buyer would have to convert the option into 100 short shares of stock. Except for ITM options with very little extrinsic value, assignment is generally uncommon – the first two options above are much more popular.

Profitability for a long put contract is realized if the contract can be sold for more than the trader bought it for up front. ITM options are more expensive than OTM options since intrinsic value is purchased up front, and that intrinsic value is retained if the stock doesn’t move. Extrinsic value always decays to zero by expiration, which is why OTM options are cheaper and more of a risky endeavor in terms of the chance of the option losing all of its value.

IN-THE-MONEY (ITM)

To find out at which point a long put trade will be profitable – i.e. the breakeven price – you should deduct the debit paid from the strike price of the option. A long put is profitable if the market price of the underlying falls below the breakeven point, or where the red turns to green in the example above.

Out-Of-The-Money (OTM)

An OTM long put option works similarly to ITM long puts. The only difference is, if the stock trades above the strike price at expiration where the trade begins, there won’t be real intrinsic value for the put owner. If this happens, the trader would lose all value paid for the option up front and realize max loss. Prior to expiration, the trader can exit the position by selling it for the market value. If it’s worth more than what they paid for it, they would realize a profit.

SELLING A PUT OPTION (SHORT PUT)

A seller of a put option assumes the opposite speculation of the put buyer. Where one profits, the other incurs a loss, and vice versa. So, a put seller’s market expectation is neutral-bullish. Therefore, they want the stock price to remain above the put strike, in which case they would keep the premium collected upfront for selling the option. This would be their profit if the contract expires worthless (OTM).

SHORT PUT OPTION ASSIGNMENT

If the right to convert a put to 100 short shares of a stock is exercised by a long put option buyer, the seller is obligated to make the exchange and “be put” 100 shares of long stock – this is called ‘assignment’. Many traders use short put options contracts to obtain 100 shares of stock at a lower cost basis than the market is offering right now.

SHORT PUT EXAMPLE

If you’re the seller in the long put example, you just want the option to expire OTM and worthless – that means your market assumption is bullish to neutral. So, you need Company XYZ’s stock price ($1,000) to remain above the strike price of $900 at expiration to realize a profit.

While it’s rare for options to be exercised, assignment would mean that you have to buy 100 physical shares of Company XYZ at the strike price – in this case, at $900 per share, selling a put at $900 means you assume the risk of 100 shares of stock below $900, less the premium collected up front for selling the contract.

Since your speculation was bullish or neutral, and the stock’s price fell below the strike price, you would have been incorrect on your directional assumption. Still though, you have the ability to obtain 100 shares of stock at a lower basis of $900 vs the $1,000 market price on trade entry, and you still keep the extrinsic value premium. Losses may still be realized though, so it’s important to be comfortable with risk on trade entry. If the stock price remains well above the strike price through expiration, you’d keep the credit received up front as profit. You’d get to keep the premium (or credit received) of $500 without having to exchange 100 physical shares of the stock in this example.

PUT OPTION VS CALL OPTIONS: WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENCES

Options contracts can either be one of two types: puts or calls. Each type can be traded individually, or as part of options strategies such as vertical spreads and iron condors. Building a solid understanding of how puts and calls differ is essential in developing your options trading skills. Here are some key differences between puts and calls:

Put Options

- The contract owner has a right, without any obligation, to sell or short 100 shares of the underlying asset at the strike price of the contract

The buyer is bearish (long put), the seller is bullish (short put) - The put buyer’s directional assumption is bearish (long put), and the put seller’s market expectation is bullish (short put)

- Long puts profit when the stock price drops past the put strike; and/or IV increases

- Short puts profit when the stock price increases, goes down a little, but not past the strike, or it doesn’t move; and/or IV decreases; and/or time passes – as long as the put contract expires OTM and worthless, the short put seller realizes max profit equivalent to the credit received upfront

Call Options

- The contract owner has a right, without any obligation, to buy 100 shares of the underlying asset at the strike price of the contract

- The call buyer’s market speculation is bullish (long call), and the call seller’s directional assumption is bearish (short call)

- Long calls profit when the stock price goes up and exceeds the strike

- Short calls profit when the stock price decreases, goes up a little, but not past the strike, or it doesn’t move; and/or IV decreases; and/or time passes – as long as the contract expires OTM and worthless, the short call seller realizes max profit equivalent to the credit received upfront

BUYING A PUT OPTION VS SHORTING STOCK

Buying a put option and shorting a stock outright differ in several ways. Let’s look at some of the main differences:

BUYING PUT OPTIONS

- Can short-sell underlying assets, including stocks, at a price higher than the market price for a profit if the put is exercised ITM

- Closing a long put position can happen three ways, which are tied to the contract’s expiration date

- Greater flexibility through variables such as strike price, expiration and options strategies

- The maximum loss is the premium paid up front for the long put (subject to trade management) – this excludes any additional fees

SHORTING STOCKS

- Can short underlying assets such as stocks outright at the market price

- The only way to close a pure short stock position is by buying back the shares; short shares have no expiration date

- Less flexibility with a static short stock position

- The maximum loss is undefined, as there is no cap to how high a stock price can go

Put Options Summed Up

- Long put options represent a trader’s bearish market assumption

- Put options consist of three key characteristics: strike price, expiration date and premium

- Put options are derivative contacts – an agreement between two parties, a buyer and a seller, to exchange 100 shares of an underlying at a predetermined strike price, by the expiration date if the put is ITM

- The buyer of the put gets the right, without any obligation, to short 100 shares of stock at the strike price; while sellers are obligated to buy these 100 shares in the case of an assignment

- A put option can be closed in three different ways: letting the contract expire worthless, selling the contract, or exercising the put (which is rare)

- Puts contracts are similar to call contracts in flexibility, but opposite in directional assumption

FAQs

What is a put option and what is a put option example?

A put option is a contract between a buyer and a seller to exchange an underlying asset at an agreed-upon price, by a certain expiration date. A long put contract allows the trader to speculate on a bearish movement in the stock price – if the stock moves down, the put contract can gain value, which can result in profitability for the owner.

Learn more about what defines a put option and learn how put options work

When one party makes a profit, the other incurs a loss, and vice versa. Potential profits and losses depend on the price action of the stock in relation to the contract’s strike price as well as other relevant factors. Put contract owners want the stock price to go down, and the contract to move ITM. Put contract sellers want the stock price to move up, or at least not move ITM, and realize max the profit of the credit received up front if the contract expires worthless.

How do I make money on a put option?

You can make money from a put option if your speculation of the market movement is correct. As a long put holder, you can either sell the contact before expiry for a profit if there is a swift bearish movement in the stock price.

On the other hand, short put positions make money when the contract expires OTM and worthless – the premium received for selling the contract up front is the profit.

What’s the downside of a put option?

Risk is involved in all trading activity. As a put buyer, your potential loss is equivalent to the debit paid up front for the put contract. If the stock never moves past the strike price and the contract expires worthless, the trader would lose 100% of the initial debit paid up front.

As a put seller, you assume the risk of 100 shares of long stock below the strike price of the contract you sell. Many people utilize short put contracts to obtain shares at a lower cost basis than the market is offering when the put contract is sold, and if the market has a huge rally, the profit is capped at the credit received. This may be seen as a negative compared to long stock owners, who realize a larger profit than a short put on a big rally in the stock price.

Why would I sell a put option?

Selling a put option is a bullish position, as you are betting against the movement of the stock price below your strike price– so, you’d sell a put if you think that the underlying’s price will rise. If the underlying’s price does, indeed, increase and the short option expires OTM, you’d make a profit. Whereas, if the market moves against you and the underlying’s price drops past the put strike by more than the credit received up front, you’d incur a loss.

When should I exercise a put option?

Put options are typically exercised automatically if they are $0.01 ITM at expiration, which means that the long put owner would then be short 100 shares of stock. Put owners exercise the contract if they want to be short 100 shares of stock instead of selling the contract to close the position.

Can I buy a put option without owning stock?

Yes, you can buy a put option without owning the physical underlying stock. Traders that use put options in this manner are typically speculating on a bearish stock price movement prior to expiration. Options allow traders to “rent” 100 shares of long or short stock, depending on whether they’re using calls or puts, for a limited amount of time. This is how the premium paid up front can be so low relative to buying/shorting shares outright in the market.

tastylive content is created, produced, and provided solely by tastylive, Inc. (“tastylive”) and is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, trading or investment advice or a recommendation that any security, futures contract, digital asset, other product, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any person. Trading securities, futures products, and digital assets involve risk and may result in a loss greater than the original amount invested. tastylive, through its content, financial programming or otherwise, does not provide investment or financial advice or make investment recommendations. Investment information provided may not be appropriate for all investors and is provided without respect to individual investor financial sophistication, financial situation, investing time horizon or risk tolerance. tastylive is not in the business of transacting securities trades, nor does it direct client commodity accounts or give commodity trading advice tailored to any particular client’s situation or investment objectives. Supporting documentation for any claims (including claims made on behalf of options programs), comparisons, statistics, or other technical data, if applicable, will be supplied upon request. tastylive is not a licensed financial adviser, registered investment adviser, or a registered broker-dealer. Options, futures, and futures options are not suitable for all investors. Prior to trading securities, options, futures, or futures options, please read the applicable risk disclosures, including, but not limited to, the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options Disclosure and the Futures and Exchange-Traded Options Risk Disclosure found on tastytrade.com/disclosures.

tastytrade, Inc. ("tastytrade”) is a registered broker-dealer and member of FINRA, NFA, and SIPC. tastytrade was previously known as tastyworks, Inc. (“tastyworks”). tastytrade offers self-directed brokerage accounts to its customers. tastytrade does not give financial or trading advice, nor does it make investment recommendations. You alone are responsible for making your investment and trading decisions and for evaluating the merits and risks associated with the use of tastytrade’s systems, services or products. tastytrade is a wholly-owned subsidiary of tastylive, Inc.

tastytrade has entered into a Marketing Agreement with tastylive (“Marketing Agent”) whereby tastytrade pays compensation to Marketing Agent to recommend tastytrade’s brokerage services. The existence of this Marketing Agreement should not be deemed as an endorsement or recommendation of Marketing Agent by tastytrade. tastytrade and Marketing Agent are separate entities with their own products and services. tastylive is the parent company of tastytrade.

tastyfx, LLC (“tastyfx”) is a Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) registered Retail Foreign Exchange Dealer (RFED) and Introducing Broker (IB) and Forex Dealer Member (FDM) of the National Futures Association (“NFA”) (NFA ID 0509630). Leveraged trading in foreign currency or off-exchange products on margin carries significant risk and may not be suitable for all investors. We advise you to carefully consider whether trading is appropriate for you based on your personal circumstances as you may lose more than you invest.

tastycrypto is provided solely by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. tasty Software Solutions, LLC is a separate but affiliate company of tastylive, Inc. Neither tastylive nor any of its affiliates are responsible for the products or services provided by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. Cryptocurrency trading is not suitable for all investors due to the number of risks involved. The value of any cryptocurrency, including digital assets pegged to fiat currency, commodities, or any other asset, may go to zero.

© copyright 2013 - 2025 tastylive, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Applicable portions of the Terms of Use on tastylive.com apply. Reproduction, adaptation, distribution, public display, exhibition for profit, or storage in any electronic storage media in whole or in part is prohibited under penalty of law, provided that you may download tastylive’s podcasts as necessary to view for personal use. tastylive was previously known as tastytrade, Inc. tastylive is a trademark/servicemark owned by tastylive, Inc.