Filter

Calendar Spread: Everything You Need to Know

What's a Calendar Spread?

A calendar spread is a strategy used in options and futures trading: two positions are opened at the same time – one long, and the other short. Calendar spreads are also known as ‘time spreads’, ‘counter spreads’ and ‘horizontal spreads’. In the options strategy version, calendar spreads are set up within the same underlying asset and strike price, but different expiration dates. In futures, this strategy is only utilizing two (or more) different expiration dates and (typically) doesn't include the buying and selling of call and put options. This piece focuses on options calendar spreads.

This strategy is ordinarily used when the directional assumption of the underlying is neutral, i.e. used in the lowest of implied volatility (IV) environments. But, it can also be successful when you’re a little bit bullish or bearish. When your speculation is that the market will be neutral, but you think the underlying price might move up slightly, you’d go for an out-of-the-money (OTM) call calendar. Whereas if you’re neutral, but you’re mildly bearish, you’d go for an OTM put calendar.

Either way, to try and collect more premium (and reduce the cost basis) of the long option you’re buying, you’d sell the nearest OTM call or put (short position). You’d then use the same strike price on the long position that’s further out in time. If you use different strike prices, it wouldn’t be a calendar spread – it would be a diagonal spread.

Learn how to set up calendar or diagonal spreads on tastytrade

But, if you think there’ll be minimal movement in the underlying’s price (i.e. not really bullish or bearish), you could go for at-the-money (ATM) options. The idea is that the long option retains or gains extrinsic value, and the short option loses extrinsic value as time passes. This is a pure extrinsic value trade, as both the long and short option are on the same strike, cancelling out any intrinsic value if the spread moves in-the-money (ITM).

Strategy Overview

DEFINITION

A calendar spread is a low-risk, directionally neutral strategy that profits from the passage of time and/or an increase in implied volatility.

DIRECTIONAL ASSUMPTION

IDEAL IMPLIED VOLATILITY ENVIRONMENT

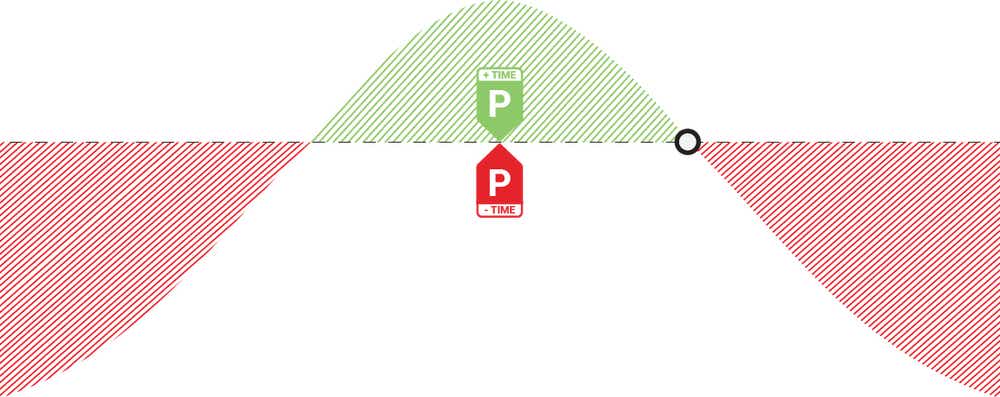

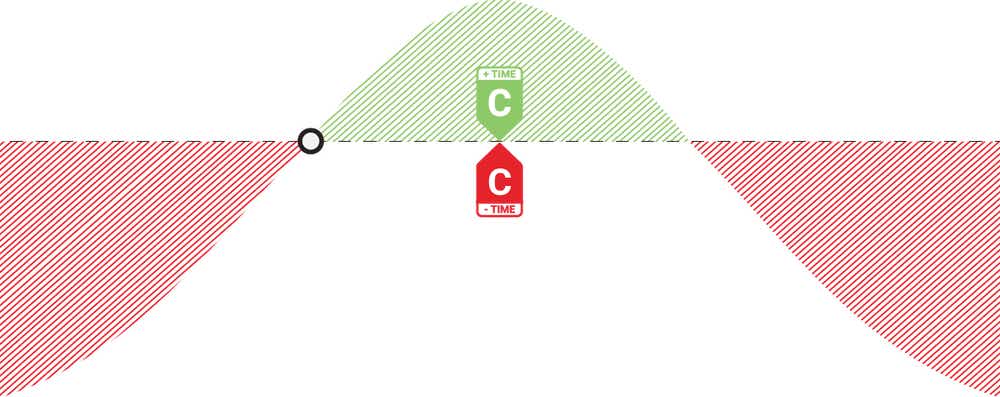

PROFIT/LOSS CHART

Put Calendar Spread

Call Calendar Spread

CALENDAR SPREAD STRATEGY IN OPTIONS TRADING: HOW IT WORKS

The calendar spread strategy works by entering a short option (call or put) in a near-term expiration cycle, and a long option (call or put) in a longer-term expiration cycle on the same underlying asset. Both options are of the same type (either call or put) and use the same strike price.

While it’s possible to have the long option in a near-term cycle, and the short option with a longer-term expiration date, this generally requires a lot of capital since the extrinsic value risk is now in the short option. So, this route kind of flies in the face of an essential part of the calendar spread – being a strategy with one of the lowest capital requirements.

Buying the longer-term option and selling the shorter-term option increases capital efficiency, which means it doesn’t require a lot of buying power – making it suitable for individual retirement accounts (IRAs). This capital relief wouldn’t apply if your short option’s duration exceeded the expiration cycle of the long option. Further, more rapid time decay in the short, near-term option (higher theta) than in the longer-term option that’s bought is typically how a profit is made in a calendar spread.

SETUP

LONG CALENDAR SETUP (TYPICAL)

SHORT CALENDAR SETUP (LESS COMMON)

HOW TO CALCULATE MAX PROFIT AND BREAKEVEN(S)

The exact maximum profit potential and breakeven cannot be calculated due to the differing expiration cycles used. However, the profit potential and breakeven area can be estimated with the following guidelines.

MAX PROFIT

One of the most positive outcomes for a calendar spread is for the trade to double in price

BREAKEVEN(S)

A guideline we use is within 1 strike of the calendar spread’s strike price

tastylive Approach

There are two things to remember when it comes to calendar spreads:

Keeping this information in mind is most helpful when setting up the trade. We pick strikes that are near the stock price, if not right on the stock price. We may skew it slightly bullish or slightly bearish if we have a small directional assumption, but it will be very close to the stock price regardless – that gives us the most exposure to profit or loss with changes in implied volatility. You will only see us routing this strategy in the lowest of IV environments.CLOSE/MANAGE

WHEN TO CLOSE

Since a calendar spread can be hurt by too much stock movement, we tend to manage our winners at around 25% of the debit we paid to enter the trade. Waiting too long for additional profits could mean stock price movement, which can be bad for the position. We never route calendar spreads in volatility instruments. Each expiration acts as its own underlying, so our max loss is not defined.

WHEN TO MANAGE

Since this is a debit spread with defined risk, we don’t usually manage it. We are comfortable with the debit paid as max loss, and there’s not much we can do with these spreads regardless since they share the same strike.

Calendar Spread Examples

Let’s move into practical territory and unpack calendar spread examples. Before we jump in, remember that the ideal route for capital efficiency is selling a short-term option and buying the longer-term option on the same strike. This way you’d benefit from the low capital requirement of the calendar spread strategy.

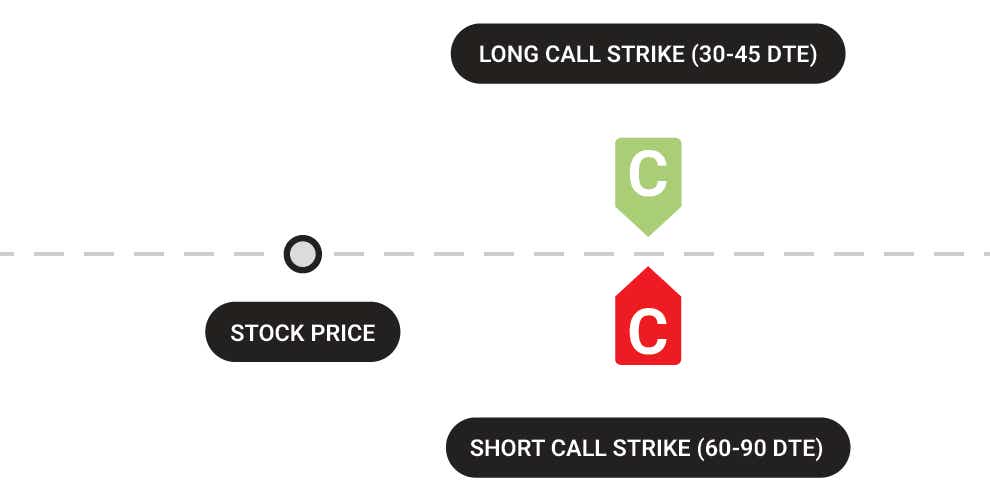

LONG CALL CALENDAR SPREAD EXAMPLE

Suppose you’re neutral but mildly bullish on Company XYZ. You enter a long calendar spread with calls when shares of the stock are trading at $50.00 – you buy a 55 call with 90 days to expiration (DTE) and sell a 55 call that expires in 45 days.

You pay a premium of $5.00 for the long position and receive a premium of $3.00 for the short call, giving you a net premium (debit) of $2.00. This would be $200.00 in total as one options contract represents 100 shares – $200.00 would also be the maximum possible loss for your calendar spread.

Fast-forward 45 days, the short option expires worthless when the underlying’s price increases to $53.00. Since the short call position is bearish, and the new market price is below the strike price, this option expires OTM.

In this case, if the long option is worth more than $2.00, you’d see a profit on your overall position, since you paid $2.00 upfront for the calendar spread. If the remaining long $55.00 call, that still has 45 DTE is worth $3.00, you’d have a net profit of $1.00, or $100.00 in real-dollar terms. You paid $200.00 for the calendar spread, the short call expired worthless, and now your long call that remains is worth $300.00.

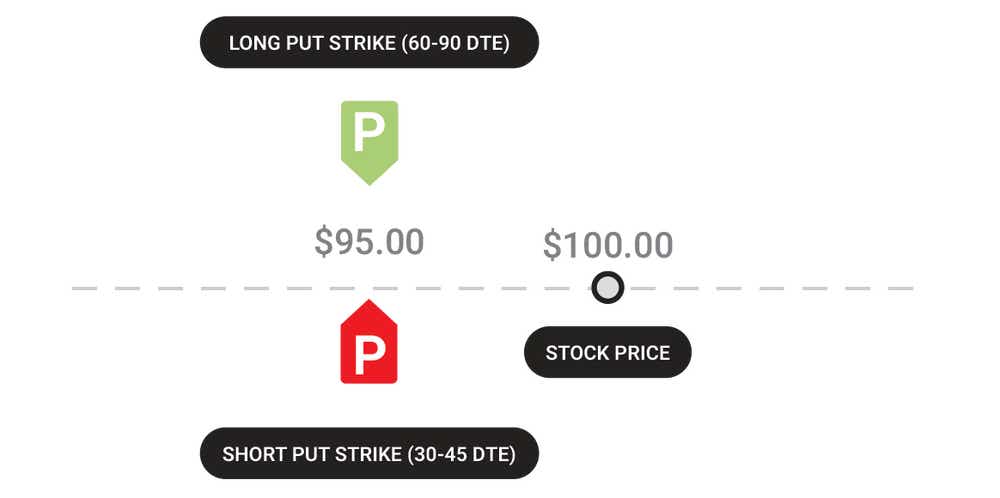

LONG PUT CALENDAR SPREAD EXAMPLE

In a long put calendar spread, you’d also have two positions with the same strike price: sell the front-month option with 30 to 45 DTE, and buy the back-month option, with 60 to 90 days to expiration. The net premium would be a debit, just like in long call calendar spreads.

Suppose you’re neutral, but mildly bearish on Company XYZ. You enter a long calendar spread with puts when its shares are trading at $100.00 – you buy a 95-strike put with 90 DTE and sell a 95-strike put that expires in 45 days.

You pay a premium of $9.00 for the long put position and receive a premium of $4.00 for the short put, giving you a net premium (debit) of $5.00. This would be $500.00 in total as one options contract represents 100 shares – $500.00 would also be the maximum possible loss for your calendar spread.

The short option expires worthless (in 45 days) when the underlying’s price drops to $96.00. Since the short put position is bullish, and the new market price is above the strike price, this option expires OTM and worthless.

In this case, if the long option is still worth $7.00, you’d see a profit on your overall position, since you paid $5.00 upfront for the calendar spread. If the remaining long 95 strike put (that still has 45 DTE) is worth $7.00, you’d have a net profit of $2.00, or $200.00 in real-dollar terms. You paid $500.00 for the calendar spread, the short put expired worthless, and now your long put that remains is worth $700.00.

SHORT CALENDAR SPREAD WITH CALLS AND PUTS

In a short calendar spread, there are two positions with the same strike price: sell the back-month option, e.g. with 60 to 90 DTE, and buy the front-month option, e.g. 30 to 45 days to expiration. So, the net premium would be a credit.

Potential profits are limited to the credit received upfront with a short calendar spread. Losses are somewhat unknown as we can’t predict a large spike in IV% in the short option, which would send the extrinsic value through the roof. The short calendar spread could be viewed as short-term delta protection against the short option, where the long calendar spread could be viewed as a cost-basis reduction against the long option you own. Both calendar spread variations are pure extrinsic value trades.

So, how do short calendar spreads differ from long calendar spreads?

Short calendar spreads with calls and puts profit from bigger movements of the underlying’s price (away from the strike price); long calendar spreads profit from smaller movements near the strike price.

Another key difference between a short calendar spread and a long calendar spread is that the options are swapped around on the basis of DTE.

Short calendar spread with calls

The near-term is the long call option (insurance against intrinsic value losses on the short call if it moves ITM); whereas the longer-term position is the short call (which has the most extrinsic value, and holds all the potential profit)

Short calendar spread with puts

The near-term is the long put option (insurance against intrinsic value losses on the short put if it moves ITM); whereas the longer-term position is the short put (which has the most extrinsic value, and holds all the potential profit)

CALENDAR SPREAD PROFIT AND LOSS

Calendar spreads’ probability of success is around the mid-forties – which isn’t that bad considering that you can’t lose very much using this strategy. The reason why it’s not a very high probability strategy is because these are pure extrinsic value trades. You cannot have the stock price go too far away from the strike price. If that happens, extrinsic value starts to go away, and the trade becomes a loser.

The typical calendar spread, selling the near-term call or put, and buying the longer-term call or put, profits when there’s:

- Positive theta decay with the stock near the strikes, i.e. making money due to the passage of time (time decay)

- Little to no movement in the underlying’s price, or a drift towards the strikes (positive gamma)

- An increase in IV, or a combination of any of the three

Keeping this information in mind is most helpful when setting up the trade. So, strikes should be near the stock price, if not right on the stock price. While it may be skewed slightly bullish or slightly bearish if you have a small directional assumption, it should still be very close to the stock price regardless.

With the probability of success being around the mid-forties, seasoned traders usually have a smaller profit target – the ideal range is 10% to 25% of the premium paid. The success rate for making above 25% of the premium paid is lower but making below 10% usually doesn’t pay enough.

The break-even for a calendar spread cannot be calculated due to the different expiration cycles being used. The long option will still remain when the short option expires, and we don’t know how much extrinsic value that option will have.

CALENDAR SPREADS IN OPTIONS SUMMED UP

- An options calendar spread is a risk-averse strategy that consists of either two calls or puts (one long and one short)

- Selling the near-term expiration and buying the long-term expiration results in a low-cost debit trade

- Calendar spreads don’t use up too much buying power – so, they can be efficient IRA trades

- Both long and short strike prices are the same for both parts of a calendar spread, but the expiration dates are different

- A calendar spread is a neutral directional assumption strategy, which makes it great for stable markets, but you can also profit if you’re slightly bullish or bearish

- Calendar spreads are suitable for low IV environments (little to no movement in the underlying’s price) – they also benefit from the passage of time and/or an increase in IV, as long as the stock stays near the strikes

FAQs

When should I buy a calendar spread?

Calendar spreads could be the way to go if you’re looking for a low capital requirement strategy (not too much buying power). But don’t forget the essentials – having a neutral directional assumption on an asset with low volatility and a stock price that you think won’t move around too much.

What’s a put calendar spread?

A long put calendar spread is a neutral-bearish options strategy where an OTM put option is purchased in a long-term expiration, and the same strike OTM put option is sold in a near-term expiration cycle.

Two put positions (short and long), with the same strike price and different expiration dates, are required to form a put calendar spread. Since the options are on the same strike, this is a pure extrinsic value trade where you want the long option to retain or gain extrinsic value, and you want the short option to expire worthless.

How do you manage calendar spreads?

The typical calendar spread is a debit spread, with defined risk. If you’re comfortable with the net premium (debit paid) as maximum loss, you don’t have to manage the spread.

Since too much stock movement is bad news for a calendar spread, managing winners around 10% to 25% of the total debit paid for a calendar is often the best way to secure profit without holding the trade too long. Profit targets outside this range means not receiving enough (under 10%) or facing a low success rate (above 25% doesn’t happen regularly enough).

How do I sell calendar spreads?

Selling a calendar spread simply refers to short calendar spreads with calls or puts, where the short option has a long-term expiration and the long option has a near-term expiration that’s purchased to define intrinsic value risk on the short option.

What’s a double calendar spread?

A double calendar spread is simultaneously purchasing two sets of a standard calendar spread that are based on the same underlying – that means four options contracts in total – for increased exposure. While a single calendar spread has only one option type, either call or put, a double calendar spread has both.

Here’s an example of a double calendar spread:

- Sell 10 XYZ June 40 strike calls

- Sell 10 XYZ June 30 strike puts

- Purchase 10 XYZ August 40 strike calls

- Purchase 10 XYZ August 30 strike puts

Are calendar spreads bullish?

Call calendar spreads can be set up to be slightly bullish. Moving the strikes slightly OTM will reduce the cost of the overall spread, but increase the potential for the long option to gain a higher value on a % basis if the stock moves towards the strikes.

What’s the risk of calendar spreads?

Waiting too long for additional profits could mean more stock price movement, which typically is bad for long calendar spreads. The true risk is the debit paid upfront, if the spread expires worthless.

In the case of short calendar spreads, which aren’t as popular as long calendar spreads, risk exposure is magnified as the remaining short contract essentially becomes a naked option once the near-term option expires.

What’s a short calendar spread?

A short calendar spread is purchasing two options of the same kind, one long and one short, at the same time and choosing a later-dated expiration month for the short position. Both the underlying and the strike prices, however, would be the same. The long option acts as short-term insurance on the short option’s intrinsic value risk if it goes ITM.

What’s a long calendar spread?

A long calendar spread is a strategy where two options that were entered into simultaneously, have different expiration dates: the short option expires sooner than the long option of the same type. But, the underlying asset and strike prices will be identical in each position. The long option is the asset in this setup, and we want it to either maintain its value, or increase in value, as the short option decays over time.

Supplemental Content

Episodes on Calendar Spread

No episodes available at this time. Check back later!

tastylive content is created, produced, and provided solely by tastylive, Inc. (“tastylive”) and is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, trading or investment advice or a recommendation that any security, futures contract, digital asset, other product, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any person. Trading securities, futures products, and digital assets involve risk and may result in a loss greater than the original amount invested. tastylive, through its content, financial programming or otherwise, does not provide investment or financial advice or make investment recommendations. Investment information provided may not be appropriate for all investors and is provided without respect to individual investor financial sophistication, financial situation, investing time horizon or risk tolerance. tastylive is not in the business of transacting securities trades, nor does it direct client commodity accounts or give commodity trading advice tailored to any particular client’s situation or investment objectives. Supporting documentation for any claims (including claims made on behalf of options programs), comparisons, statistics, or other technical data, if applicable, will be supplied upon request. tastylive is not a licensed financial adviser, registered investment adviser, or a registered broker-dealer. Options, futures, and futures options are not suitable for all investors. Prior to trading securities, options, futures, or futures options, please read the applicable risk disclosures, including, but not limited to, the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options Disclosure and the Futures and Exchange-Traded Options Risk Disclosure found on tastytrade.com/disclosures.

tastytrade, Inc. ("tastytrade”) is a registered broker-dealer and member of FINRA, NFA, and SIPC. tastytrade was previously known as tastyworks, Inc. (“tastyworks”). tastytrade offers self-directed brokerage accounts to its customers. tastytrade does not give financial or trading advice, nor does it make investment recommendations. You alone are responsible for making your investment and trading decisions and for evaluating the merits and risks associated with the use of tastytrade’s systems, services or products. tastytrade is a wholly-owned subsidiary of tastylive, Inc.

tastytrade has entered into a Marketing Agreement with tastylive (“Marketing Agent”) whereby tastytrade pays compensation to Marketing Agent to recommend tastytrade’s brokerage services. The existence of this Marketing Agreement should not be deemed as an endorsement or recommendation of Marketing Agent by tastytrade. tastytrade and Marketing Agent are separate entities with their own products and services. tastylive is the parent company of tastytrade.

tastyfx, LLC (“tastyfx”) is a Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) registered Retail Foreign Exchange Dealer (RFED) and Introducing Broker (IB) and Forex Dealer Member (FDM) of the National Futures Association (“NFA”) (NFA ID 0509630). Leveraged trading in foreign currency or off-exchange products on margin carries significant risk and may not be suitable for all investors. We advise you to carefully consider whether trading is appropriate for you based on your personal circumstances as you may lose more than you invest.

tastycrypto is provided solely by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. tasty Software Solutions, LLC is a separate but affiliate company of tastylive, Inc. Neither tastylive nor any of its affiliates are responsible for the products or services provided by tasty Software Solutions, LLC. Cryptocurrency trading is not suitable for all investors due to the number of risks involved. The value of any cryptocurrency, including digital assets pegged to fiat currency, commodities, or any other asset, may go to zero.

© copyright 2013 - 2025 tastylive, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Applicable portions of the Terms of Use on tastylive.com apply. Reproduction, adaptation, distribution, public display, exhibition for profit, or storage in any electronic storage media in whole or in part is prohibited under penalty of law, provided that you may download tastylive’s podcasts as necessary to view for personal use. tastylive was previously known as tastytrade, Inc. tastylive is a trademark/servicemark owned by tastylive, Inc.