Why The Latest Bank Failure is Different and Could Be a Turning Point

Why The Latest Bank Failure is Different and Could Be a Turning Point

The collapse may signal a shake-up for depositors and a need for new strategies

- Following the collapse of First National Bank of Lindsay in Oklahoma, regulators have signaled a potential policy shift that may raise concern for depositors.

- If regulators decide not to cover all of the bank’s uninsured deposits, customers may shift their accounts to larger financial institutions.

- As regulatory priorities change, individuals and businesses may need to reassess their banking strategies to minimize exposure to losses.

Two community bank failures in a single year may not signal an immediate crisis but could serve as a stark reminder of underlying fragility in certain segments of the financial system.

The latest collapse occurred Oct. 18 when federal regulators shut down the First National Bank of Lindsay. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) said “false and deceptive records,” made the Oklahoma community bank an “unsafe and unsound condition to transact business,” with liabilities exceeding its assets. Just three days later, the bank reopened under the new ownership of First Bank & Trust Company—which is based in Duncan, Oklahoma.

Although it’s only the second bank failure of the year, the collapse of First National Bank of Lindsay highlights the vulnerabilities of smaller financial institutions. With deposits of $97.5 million, the bank was relatively minor, yet its failure still triggered intervention by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Early estimates suggest the failure will cost the FDIC around $43 million.

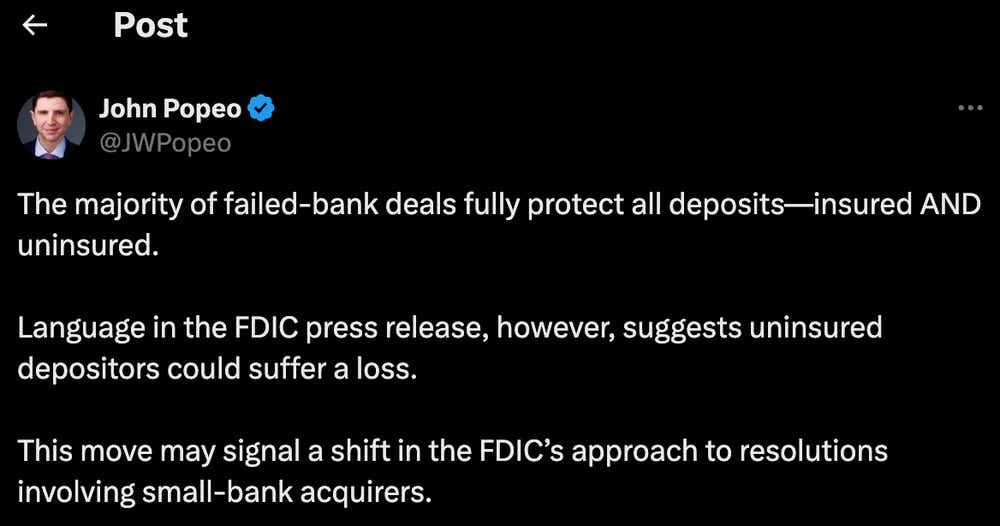

What makes this failure notable is the regulatory response: unlike recent high-profile collapses, such as Silicon Valley Bank, regulators have signaled they won’t immediately backstop all of the uninsured deposits. If that approach holds, it could mark a turning point for how smaller bank failures are managed, with potentially far-reaching consequences for depositors and investors alike.

Why this failure is different

One crucial element of any bank failure is the role played by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). It was established in 1933 to insure deposits up to $250,000 per account for individuals and businesses. This limit has protected the most depositors and offered stability in times of uncertainty. However, for wealthier individuals or businesses with deposits exceeding $250,000, the risk can become pronounced.

Because the current round of banking instability began in March 2023 with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the FDIC and other regulators have gone above and beyond their stated mandate. In several high-profile failures—including Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank—regulators backstopped not only insured deposits but also those that exceeded the $250,000 threshold.

This approach, designed to stave off broader financial panic, ensured even uninsured deposits were covered, helping to restore confidence in the banking system. However, the failure of First National Bank of Lindsay could mark a significant departure from this approach. The FDIC is backing up only a portion of deposits of more than $250,000

“Based on the estimated recoveries of the failed bank assets, the FDIC will make 50% of uninsured funds available to those depositors on Monday, Oct. 21, 2024,” the regulatory agency said in a statement. “This amount could increase as the FDIC sells the assets of the failed bank.”

This policy may reflect a new regulatory strategy aimed at drawing a line between small local banks and larger institutions whose failures might pose systemic risks. While larger banks have benefited from sweeping government intervention, smaller banks appear to be navigating a stricter landscape, where the consequences of risky business practices fall squarely on them and their depositors.

Reassessing deposit risk

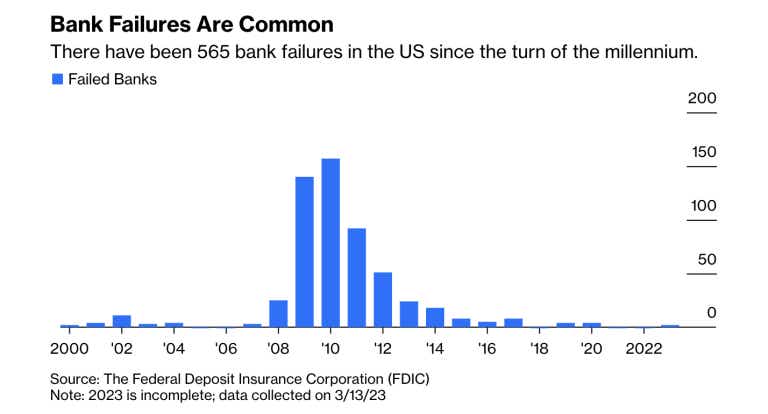

Despite the failure of First National Bank of Lindsay, the broader financial system remains stable. Third-quarter earnings reports indicate the nation’s largest financial institutions are successfully navigating the economic landscape. Although a few banks have failed in 2023 and 2024, the overall number remains low by historical standards, as illustrated below.

Despite the relative stability, the latest bank failure, and associated regulatory response, could mark a turning point for depositor confidence. Traditionally, many depositors with balances exceeding the FDIC’s $250,000 insurance limit may have felt secure and assumed uninsured deposits might still be covered. This recent decision signals a potential shift in regulatory priorities.

For some depositors, this may prompt a more strategic approach to safeguarding their funds. To ensure full FDIC coverage, individuals and businesses may choose to spread deposits across multiple accounts at different institutions, keeping each account below the $250,000 limit. Others may perceive large banks as safer options, consolidating funds where recent trends suggest a higher likelihood of regulatory support for uninsured deposits.

This quest for stability could lead to a significant capital migration, as funds shift from smaller banks to larger institutions. Moreover, this process could place added strain on community and regional banks, which rely heavily on customer deposits for funding. To compete, smaller banks may need to offer higher interest rates or new incentives to retain and attract depositors.

For both individuals and businesses, this highlights the importance of reassessing banking relationships and managing potential risk to deposits. Securing one’s capital may require a more diversified and vigilant approach.

Andrew Prochnow has more than 15 years of experience trading the global financial markets, including 10 years as a professional options trader. Andrew is a frequent contributor of Luckbox Magazine.

For live daily programming, market news and commentary, visit #tastylive or the YouTube channels tastylive (for options traders), and tastyliveTrending for stocks, futures, forex & macro.

Trade with a better broker, open a tastytrade account today. tastylive, Inc. and tastytrade, Inc. are separate but affiliated companies.

Options involve risk and are not suitable for all investors. Please read Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before deciding to invest in options.