Debt Ceiling: The US Will Not Default. What’s Next for Markets?

Debt Ceiling: The US Will Not Default. What’s Next for Markets?

We’ve seen this movie, right? The US is on the verge of a catastrophic debt ceiling breach, which will lead to a US default (at least, technically speaking), and lawmakers in Washington, D.C. just can’t seem to get their acts together.

But after several weeks of playing a game of chicken, Democrats and Republicans announce that a deal has been struck that will prevent the US from making one of the worst self-inflicted economic and financial wounds in history.

At least, that’s what happened to varying degrees in 2011, 2013, 2017, and more recently, in 2019. And while no official deal has been struck thus far, it appears that we’re on the path to another ‘close, but no cigar’ US default in 2023.

What is the TGA?

For all the ink spilled over what a US default may bring to financial markets, not much has been said about what financial markets may look like on the other side of a deal to avert calamity. To start, it’s important to understand how a US default would actually unfold.

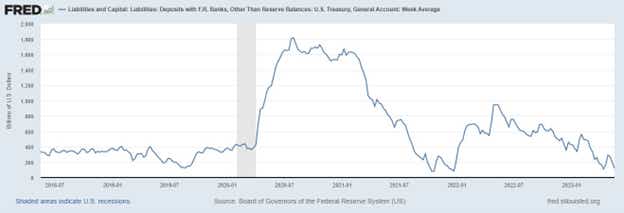

The US would default if it ran out of money to pay back its bills and obligations. How do we see how much money the US has in its accounts? We can head over to the Treasury General Account (TGA). The TGA is the general checking account, which the Department of the Treasury uses and from which the US government makes all of its official payments.

Here’s where the TGA stands as of May 10, 2023:

On the other side of a deal to avert a US default, the TGA will have to be replenished. The mechanics of how this works in the banking system are important for understanding how markets may behave over the coming weeks.

How Does the TGA Work?

When individuals or businesses receive a government check, they deposit it into their regular bank accounts. The banks then send these checks to the Fed, which then takes the money from the Treasury's account and adds it to the bank's account at the Fed. This increases the amount of money the bank has in reserves.

The TGA is listed as a liability on the Fed's financial records, along with things like physical money (like coins and notes) and bank reserves. The Fed needs to make sure that its liabilities match its assets. So, if the amount of money in the TGA goes up (say, after a US debt deal), the amount of bank reserves goes down.

When money flows into the TGA, it decreases the amount of bank reserves. A drop in bank reserves can lead to reduced liquidity for banks, potentially leading to less lending or investment in the economy or financial markets.

Replenishing the TGA Might Hurt

Bringing the TGA’s balance back to elevated levels such that the US can pay its bills and obligations should, in theory, be negative for liquidity conditions in the coming weeks. The mechanics of replenishing the TGA suggest that bonds will need to be sold in order to reestablish a more sustainable cash balance. By selling bonds, this will be akin to a quantitative tightening (QT) program, at least in the short-term.

A short-term drawdown of liquidity in financial markets centered around the selling of bonds to replenish the TGA appears to be in the cards over in the coming weeks. Theoretically, this type of environment would cater to higher US Treasury yields (weaker /ZN and /ZB), helping support a stronger US Dollar (weaker /6E and /6J), diminishing the appeal of precious metals (weaker /GC and /SI), and undercutting the initial enthusiasm seen in US equity markets (weaker /ES and /NQ). A temporary setback in risk appetite in June 2023 should not be ruled out, even as the US avoids a default.

--- Written by Christopher Vecchio, CFA, Head of Futures and Forex

Options involve risk and are not suitable for all investors. Please read Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before deciding to invest in options.